Yaman Tohme

We get out of our mother’s womb with a cry, a scream with tears as a declaration of the beginning of a life. Tears accompany our lack of language. Do we want to get out of the womb? Do we want life to enter our bodies? Why are we screaming into the ears of those who decided to bring us to life?

We, the babies, stretch our language into tears. Demanding food, love, & care. How could we tell our caregivers otherwise? How can we reach our existential needs when language is absent? We wail and cry and weep. Accompanying our tears with different pitches according to our needs. It’s our protest against this birth.

Babies crying is the managing stimulant of parental behaviors. Multiple developmental studies show that the pitch of a baby’s cry is a high factor in determining the response of the adult. It provides the listener with the “real” information behind the cry through breathing cues. Short cries with short pauses produce stimuli of high urgency unlike long cries with long pauses.

However, looking at the crying of a baby from a merely evolutionary lane is reductive. Crying as a mere language for food and physical wellbeing seems narrow. The baby is crying for more than materiality, it’s crying for love and care. When we perceive the family and community in a reduced form of a nuclear family, we would perceive the baby’s cry as a longitude for the maternal need. However, a cry can stretch beyond our narrow understanding of modern families. Our understanding is defined by the maternal connection to an infant that bestows the job of parental raising on one or two humans. When in other times – babies were cared for by communities rather than rendered into the heavy weight of one individual duty.

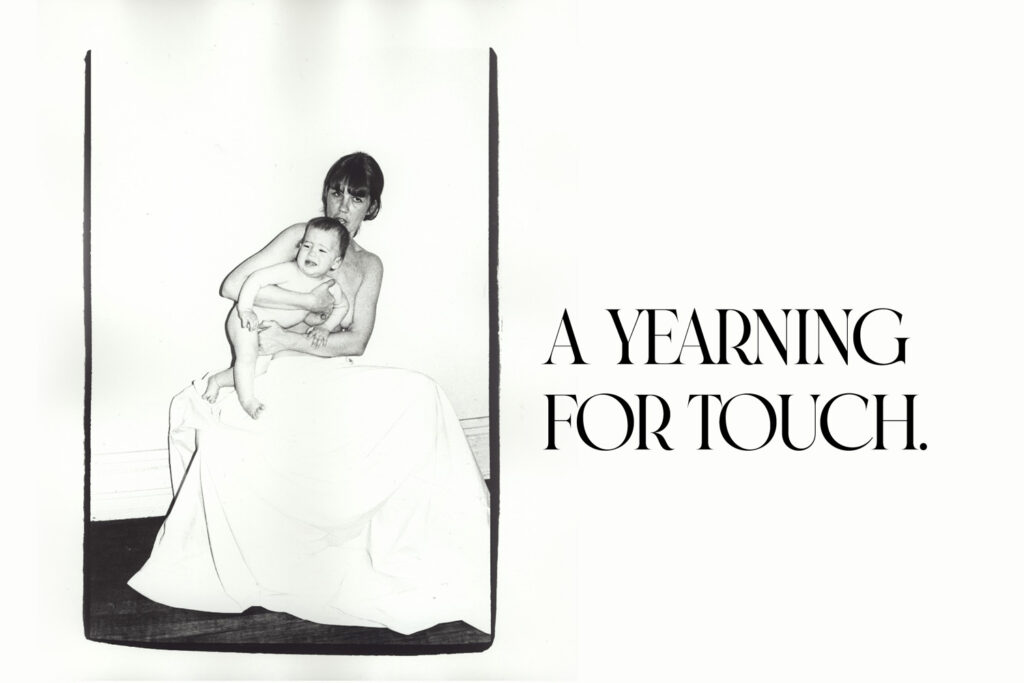

A baby cry is also a yearning for touch. It’s a yearning for a physical bond of care, to be contained in a body and to be carried for safety. Perhaps it’s the longing for return to a womb, an objection towards birth. A healthy baby in hunting/gathering peoples and primates alike, is rarely off the body of its mother or another group member. The bond might be so tight that in some primate species, dead infants are carried by their caregivers for hours even days after their death. Crying among infants is rare in cultures where they are carried constantly by their caregivers.

A crying baby is also a demand for milk, a role that has been rendered to mothers in our modern days. However, not all mothers could fulfill this need for their baby. History is filled with communities sharing milk between lactating women and babies within that community. Creating a milk-sharing system that is embedded with negotiation when the need of infants and the presence of lactating females. It’s a relationship of reciprocity beyond the nuclear family.

Perhaps a baby’s cry is an indication of our understanding of families and their constructs. A demand for reflection on our understanding of motherhood and its heavy demand. Is the parenting role bestowed on two individuals or shall it expand to constructs beyond that? A cry is to be listened to rather ignored. An indication to be read as a societal symptom to reconstruct through, rather than a voice to be silenced within the easiest material routes. Are babies telling us something? Do we, the adults, need to listen to what these cries are carrying as screams to return to a better reality?

Adults carry this confident conviction of understanding realities within better lenses than babies. Babies don’t understand the current world, which can be an advantage of a different lense to look through. Infants have the instinctive route of listening (and demanding) their needs without rendering the modern world through those needs. They give us better routes of imagining alternative realities to the constructs we reside in. We have a lot to learn from a baby’s cry.

References:

Nicholas S. Thompson, Carohn Olson, & Brian Dessureau. (1996). Babies’ Cries: Who’s Listening? Who’s Being Fooled? Social Research, 63(3), 763–784.

Cohen, D. J. (1967). The Crying Newborn’s Accommodation to The Nipple. Child Development, 38(1), 88–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1967.tb04329.x

Valman, H. B. (1980b). The first year of life. Crying babies. BMJ, 280(6230), 1522–1525. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.280.6230.1522

Messerschmidt, Franz Xaver 1736-1783. After. (18th century.). Bust of a Crying Baby. [Marble.]. Location unknown. https://jstor.org/stable/community.11966533

Green, Allen Ayrault, 1880-1963. (n.d.). Blick’s baby crying. https://jstor.org/stable/community.31981462

Andy Warhol (American painter, printmaker, and filmmaker, 1928-1987). (undated). Children [Gelatin silver print]. Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University; Gift of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. https://jstor.org/stable/community.18153933

Cory, Fanny Y. (n.d.). Tragedies of Childhood [Black and white print]. Modern Graphic History Library, Washington University in St. Louis. https://jstor.org/stable/community.16502787

Andy Warhol (American painter, printmaker, and filmmaker, 1928-1987). (undated). Mother and Child [Gelatin silver print]. Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center, University of California, Los Angeles; Gift of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. https://jstor.org/stable/community.18069526

Flagler Fruit & Packing Co. (n.d.). Cry Baby. UC Davis Library, Archives and Special Collections. https://jstor.org/stable/community.33403510

unknown. (1960 Feb). Calilica Alega and her newborn son Rogers in her hospital bed at the Veterans Memorial hospital in the Philippines. Two doctors and a nurse stand at the side of the bed, looking at the child who was named for Edith Rogers. [Non-projected black and white photograph]. https://jstor.org/stable/community.12264199