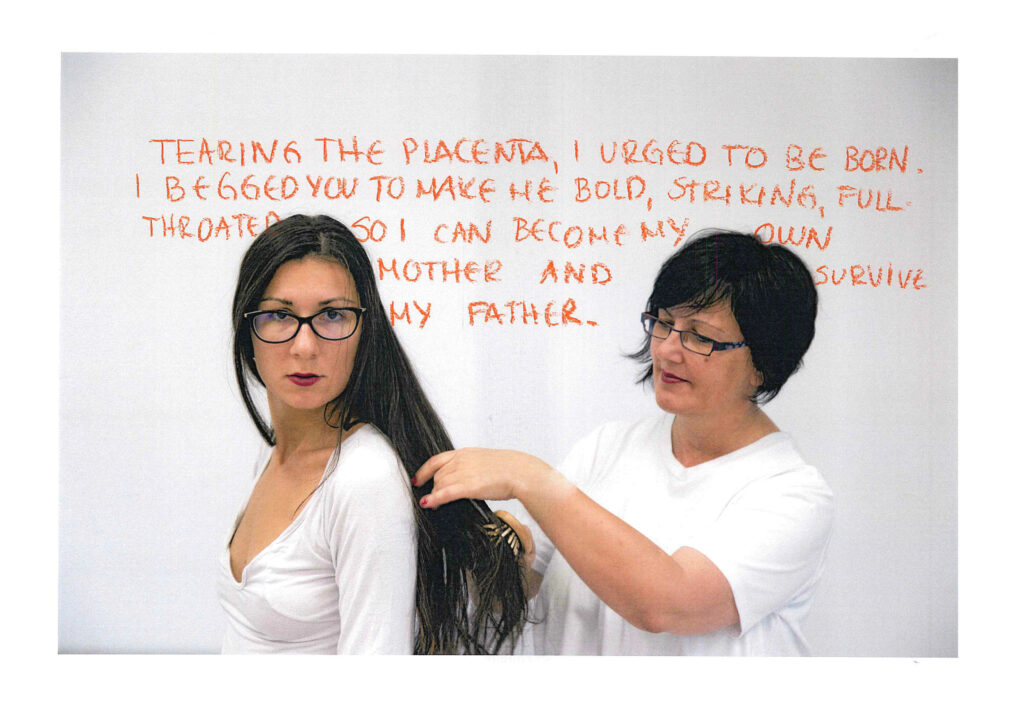

Gabriela Parra Sánchez. Weimar. 2022

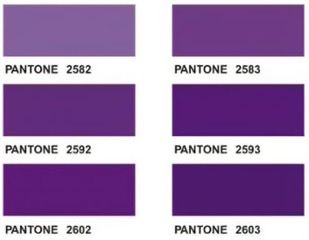

PLEASE FEEL FREE TO COMPLETE THE GLOSSARY BY SUGGESTING NEW ADJECTIVES IN THE COMMENTS:

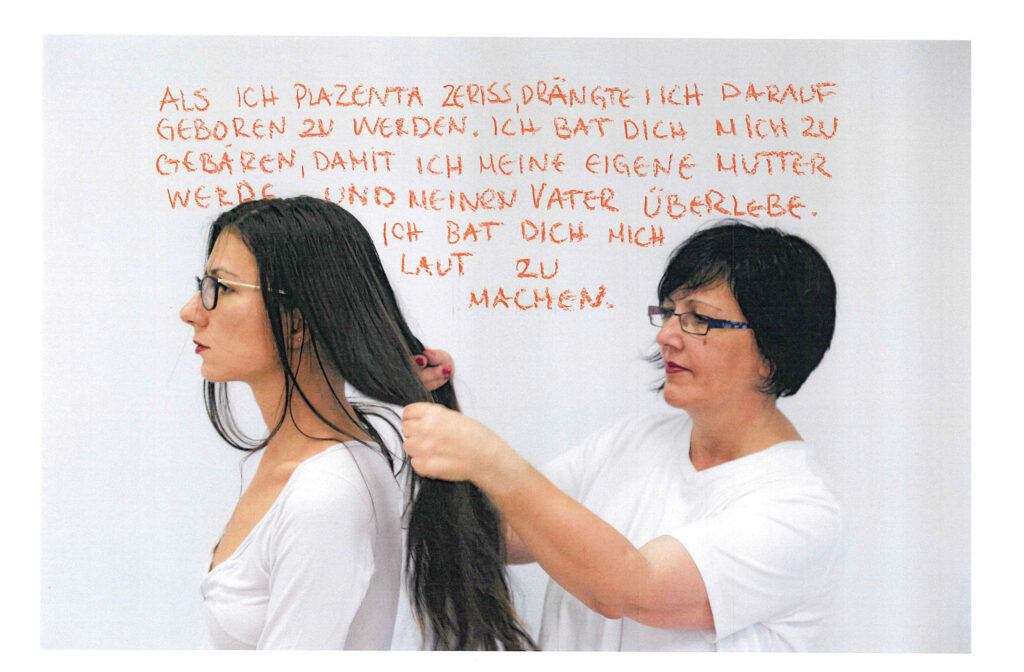

Gabriela Parra Sánchez. Weimar. 2022

PLEASE FEEL FREE TO COMPLETE THE GLOSSARY BY SUGGESTING NEW ADJECTIVES IN THE COMMENTS:

a concerning by Gabriela Parra Sánchez for the Crying Institute.

03.11.22, 5:26

I can feel them coming in the night: A warm force within my closed eyelids. Each and every time, I hope they will subside before the pressure is high enough to release them into my sleepless night. I am terrified of what will happen otherwise.

So often in the past two years, a single drop would lead to hours of crying. A silent sob, barely recognizable through unsteady and pressed breathing might build up to an open cry with soft moaning which may then escalate into a panic attack, depending on which images and thoughts well up in the outpouring. It would leave me empty, embarrassed, and exhausted, a mere shadow of my former selves. With each of these crying sessions, I would sink deeper into the darkness, awakening the ghosts of older wounds that would accompany the recent ones on their way to the surface of my eye.

So when I feel them coming, I try to suppress the transgression with breathing techniques, a softening of the face muscles, an adjustment of my posture to make more space for the wet disaster lingering on my eyeballs. I turn to discipline to force the immanent loss of control back into the realm of the unconscious. If I succeed, sleep may find me again.

Tonight, it’s just two tears on my pillow.

In ihrer Performacne “The Artist is Present” im New Yorker Museum of Modern Art 2010 teilte Marina Abramović mit jedem Menschen, der ihr gegenüber abwechselnd am Tisch saß, eine Minute der Stille. Fast drei Monate lang, acht Stunden am Tag begegneten sich die Blicke von Marina und etwa Eintausend Besucher*innen.

Plötzlich saß ihr ehemaliger Partner Ulay vor ihr …

Marina Abramović und Ulay arbeiteten und lebten von 1976 bis 1988 zusammen.

Relation in Space, 1976, aus der Serie: Relation Work 1976 – 1979, Analogvideo, Betacam SP, b/w, mono, 00:14:34, Sammlung ZKM | Zentrum für Kunst und Medien, http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/werke/relation-in-space/video/1/

Relation in Time, 1977, aus der Serie: Relation Work 1976 – 1979, Analogvideo, Betacam SP, b/w, mono, 00:11:57, Sammlung ZKM | Zentrum für Kunst und Medien, https://zkm.de/en/artwork/relation-in-time

Breathing in – Breathing out, 1977, aus der Serie: Relation Work 1976 – 1979, Analogvideo, Betacam SP, s/w, mono, 00:11:30, Sammlung: ZKM | Zentrum für Kunst und Medien, https://zkm.de/en/artwork/breathing-in-breathing-out

Breathing out – Breathing in, filmische Aufzeichnung einer vom Stedelijk Museum in Auftrag gegebenen Performance aus dem Jahr 1977, die ohne Publikum stattfand, https://www.stedelijk.nl/en/collection/9811-ulay-breathing-out-breathing-in-%28performance-10%29

Rest Energy, aufgenommen 1980 im Filmstudio Amsterdam, aus der Serie: That Self, 00:04:00, Sammlung: Netherlands Media Art Institute Amsterdam.Weiteres: https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/243/3120

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rest_Energy_(performance_piece)

Night Sea Crossing, The Observer: – le temps d’une cigarette -, 1984, aus der Serie: Modus Vivendi, Analogvideo, Betacam SP, Farbe, mono, 00:06:03, Mitwirkende: Rémy Zaugg (Drehbuch, Darsteller), Ton Illegems (Kamera), Marina Abramović (Darsteller*in), Ulay (Darsteller*in), Michael Stefanowsky (Darsteller, Sprecher), Sammlung: ZKM | Zentrum für Kunst und Medien, https://zkm.de/de/werk/night-sea-crossing

The Lovers, The Great Wall Walk, 1988, Zwei-Kanal-Video, Farbe, Ton, 16:45 Min., Stichting LIMA, Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives and Murray Grigor, based on the 1988 performance, http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/werke/the-lovers/

Später führten Abramović und Ulay einen Rechtsstreit über die Verwaltung der Urheberrechte ihrer gemeinsamen Arbeit. Abramović schuldete Ulay, wie ein Gericht in Amsterdam 2016 entschied, sowohl Schadenersatz als auch die Erwähnung seines Namen in ihren gemeinsamen Arbeiten, die Abramović bis dahin allein vermarktete (https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/21/ulay-claims-legal-victory-in-case-against-ex-partner-marina-abramovic).

Zurück zum Anfang der hier erzählten Geschichte:

Plötzlich saß ihr ehemaliger Partner Ulay im MoMA vor ihr …

Fragen:

Ändern sich Marinas Tränen in Kenntnis der Geschichte von Abramović und Ulay?

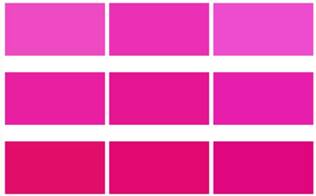

Empfinden Sie diese Tränen, die als die „bewegendsten Tränen der jüngeren Kunstgeschichte“ beschrieben werden, als kitschig, als Tränen der Rührseligkeit, des Mitgefühls, der Freude, der Überraschung, der Überwältigung, der Überforderung, des Schocks …?

Sind Marinas Tränen andere als Ulays feuchte Augen? Und andere als unsere, wenn wir geweint haben sollten?

Was erzählen diese Tränen über Marina, was über Ulay und was über uns?

…

Drei Anmerkungen zur Wahrnehmung der Wahrnehmung:

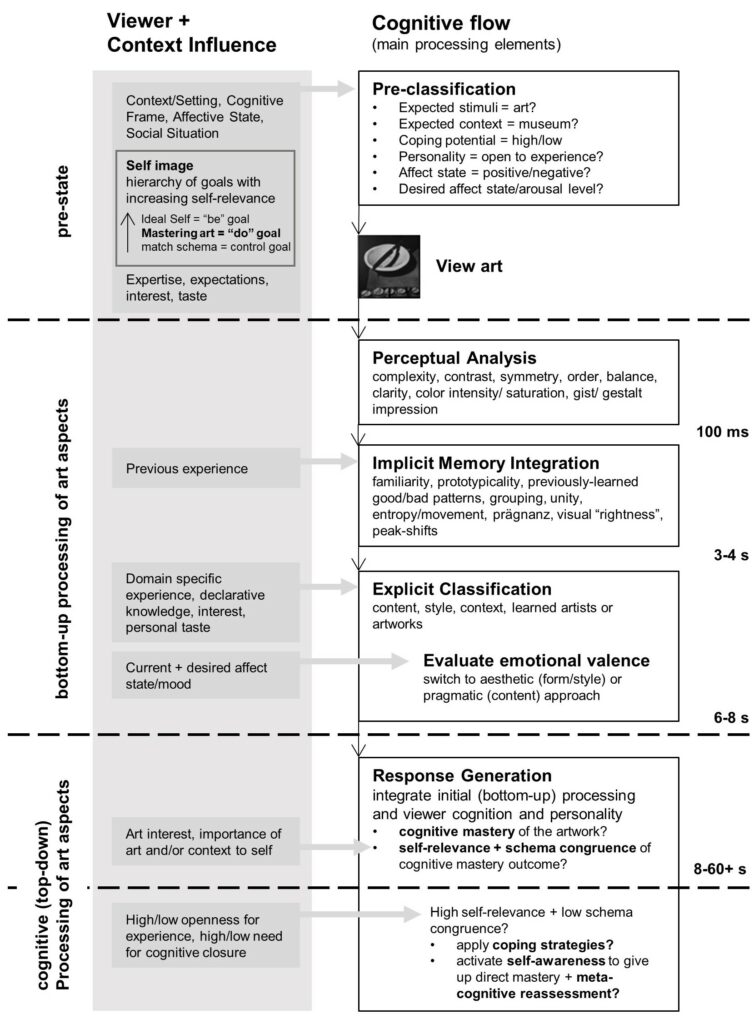

Keywords: Art perception, Cognitive model, Neuroaesthetics, Emotion, Top-down bottom-up integration

Vgl. Matthew Pelowski u. a.: Move me, astonish me… delight my eyes and brain: The Vienna integrated model of top-down and bottom-up processes in art perception (VIMAP) and corresponding affective, evaluative, and neurophysiological correlates, in: Physics of Life Reviews, Bd. 21, 2017, S. 80–125, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2017.02.003 [Abruf: 10.11.2022]

Beispiele:

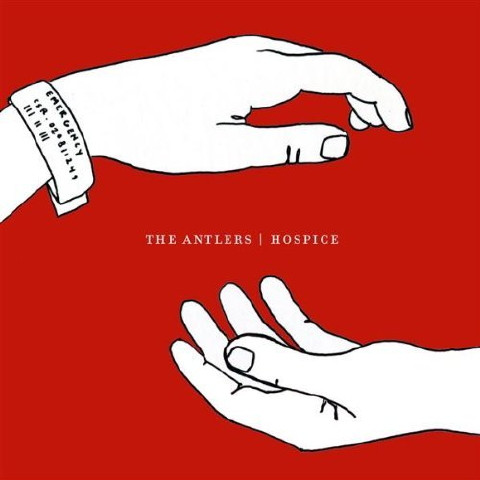

Released in 2009, Hospice in the third studio album by the Brooklyn-based indie rock band, The Antlers. An album that has been described by the NME as “the saddest album of all time”. The album title alone – on the blood-red album cover featuring two hands, yearning to hold each other for eternity – engulfs me with a sense of melancholy. I do believe that the saddest album of all time fits the album pretty well.

The entire album, musically, could be boiled down to three songs. It takes more than one listen to be able to tell the songs apart, with the exception of a few more aggressive and fast-paced tracks. But if the songs feel the same it’s because grief feels all the same. The vocalist – Peter Silbermann -sounds like he’s broken at the core, gently whispering to himself in an abondoned parking lot, which makes the rare outburst of shouted lines feel like punch in the gut. The devastating lyrics, Silberman’s aching voice, backed by an atmospheric mixture of noise and texture and recurring melodies, makes it one of the most solid concept albums i’ve ever heard.

Hospice tells the tale of an unwieldy relationship between a hospice worker – whom I refer to as Peter, the lead singer of the band – and his dying patient, Sylvia. After an instrumental opening track comes Kettering. Peter Silberman’s low, somnambulant tone walks us through the first time Peter and Sylvia meet in a hospital room, backed by a music which is just the most painful combination of notes ever. Sylvia has tubes in her arms and morphine alarms are singing out of tune.

I wish that I had known in that first minute we met, the unpayable debt that I owed you

Kettering

Peter sounds taken back, as though he is aware of the pain this story is going to bring. Sylvia is rather hostile – telling Peter that his voice makes her feel so alone and he better leaves. Yet Peter persists – despite being told that there’s no saving her, and despite sensing that it’s not going to end pretty, she wants to help the “freezing” girl.

But something kept me standing by that hospital bed

Kettering

I should have quit, but instead, I took care of you

You made me sleep and uneven, and I didn’t believe them

When they told me that there was no saving you

Sylvia is – and sounds like – a troubled soul, and does not try to hide it. She pushes Peter back, but at the same time guilts him into staying with her.

Sylvia, get your head out of the oven

Sylvia

Go back to screaming and cursing

Remind me again how everyone betrayed you

Get your head out of the oven could be referencing Sylvia Ploth’s suicide, showing that Peter would rather for Sylvia to yell at him, than being depressed and suicidal. It’s also indicated that she gets physically violence towards Peter, while refusing to let him help her.

Let me do my job

Let me do my jobSylvia, get your head out of the covers

Sylvia

Let me take your temperature

You can throw the thermometer right back at me

If that’s what you want to do, okay?

Peter sees her struggling and it breaks him.

As the album goes by and specially in the track Anthropy, we learn more about the abusive nature of their relationship. Sylvia is trying to get control of every aspect of Peter’s life.

You’ve been living a while in the front of my skull making orders

Anthropy

You’ve been writing me rules, shrinking maps and redrawing borders

I’ve been repeating your speeches, but the audience just doesn’t follow

Because I’m leaving out words, punctuation, and it sounds pretty hollow

we also learn that they’re now married, which makes Peter feel ever more bound to her.

With the bite of the teeth of that ring on my finger, I’m bound to your bedside, your eulogy singer

Anthropy

I’d happily take all those bullets inside you and put them inside of myself

The song contains the beautiful line, “I’d happily take all those bullets inside you and put them inside of myself”, which refers to the fact that Peter still feels willing to sacrifice himself if it could make Sylvia happier

Bear is about an abortion and opens with an uncanny nursery rhyme – Sylvia is pregnant, and sheand Peter are quick to decide they don’t want to have a child, we also learn that they’ve been isolated from their friends – another sign of an abusive relationship – and do not have a support system which means they only have to lean on each other when going through this rough path.

There’s a bear inside your stomach

A cub’s been kicking from within

He’s loud, though without vocal cords

We’ll put an end to himNone of our friends will come, they dodge our calls

Bear

And they have for quite awhile now

It’s not a shock, you don’t seem to mind

And I just can’t see how

They are, Peter emphasize, not making this decision out of a fear of responsibility or financial issues, they are afraid of each other and Sylvia’s worsening conditions. This song ends with Peter admitting that they are now broken beyond repair.

Well we’re not scared of making caves

Or finding food for him to eat

We’re terrified of one another

And terrified of what that meansWhen we get home we’re bigger strangers

Bear

Than we’ve ever been before

You sit in front of snowy television

Suitcase on the floor

Thirteen is the only song being told from Sylvia’s point of view. And if you have imagined her as manipulative, narcissistic young women this is where you get a glimpse of her suffering for the first time: the whole song is her begging Peter to save her, as she is in denial of her current state and doesn’t want to see anyone, no doctors, no nurses, just peter.

Pull me out

Thirteen

Pull me out

Can’t you stop this all from happening?

Close the doors and keep them out

Two are of one the rare more fast paced songs and a very important song in my opinion. It tells the story of the day Peter is told by the doctors that Sylvia is going to die and beautifully portrays how Peter feels hearing that: as if the world is crushing around him.

To hear that there was nothing that I could do to save you

Two

The choir’s gonna sing, and this thing is gonna kill you

Something in my throat made my next words shake

And something in the wires made the light-bulbs break

There was glass inside my feet and raining down from the ceiling

It opened up the scars that had just finished healing

It tore apart the canyon running down your femur

I thought that it was beautiful, it made me a believer

We also learn a little more about Sylvia, about her childhood with an abusive father and struggling with eating disorders that no one seemed to care about.

Your daddy was an asshole and he fucked you up

Two

Built the gears in your head, now he greases them up

And no one paid attention when you just stopped eating

“Eighty-seven pounds!” and this all bears repeating

In the wake of knowing that she’s dying, Sylvia is acting out and Peter is trying to keep up with her. However this is the only point in the album where you can sense a bit of resentment in Peter’s voice, as he describes how he had to grab Sylvia’s ankles begging her to stay, and how he has stopped caring now.

It killed me to see you getting always rejected

Two

But I didn’t mind the things you threw, the phones I deflected

I didn’t mind you blaming me for your mistakes

I just held you in the door-frame through all of the earthquakes

But you packed up your clothes in that bag every night

I would try to grab your ankles, what a pitiful sight

But after over a year, I stopped trying to stop you from stomping out that door

Coming back like you always do

Perhaps unconsciously – but Peter is also admitting that his actions might have had the exact opposite of protecting Sylvia, as Contrary to popular belief, doorways are not the safest place to be during an earthquake.

Shiva describes when Sylvia dies, starting with the hauntings lines.

Suddenly every machine stopped at once

Shiva

And the monitors beeped the last time

Hundreds of thousands of hospital beds

And all of them empty but mine

The song also contains multiple indication of how he sees himself in Sylvia’s place: the roles are now reversed. I wonder, is it because of the emotional damages he has had to endure? Or is he becoming void of himself?

You checked yourself out when you put me to bed

Shiva

And tore that old band off your wrist

But you came back to see me for a minute or less

And left me your ring in my fist

My interpretation is that their lives had become tangled together in a way that Peter doesn’t recognize himself anymore. It was all about Sylvia when she was alive and now that she’s gone, it’s still all about Sylvia. The trauma might very well reproduce itself in the rest of Peter’s life – he acknowledges that now, and feels crushed by this horror beyond grasping.

My hair started growing, my face became yours

Shiva

My femur was breaking in half

The sensation was scissors and too much to scream

So instead, I just started to laugh

Wake is one of my favorite songs on the album. Peter’s voice is much calmer in this song, like how you’d feel after a good cry or a panic attack. A bit numb, but also relieved. He is trying to face Sylvia’s death and his life without her. There are lots of small but achingly hard things you need to do when someones gone. Even picking up the dirty clothes seems like a task beyond his abilities. It’s also a subtle reference to the song Sylvia, where Peter begs Sylvia to let him do his job. Well he failed. And someone has to pick up the pieces.

With the door closed, shades drawn, the world shrinks

Wake

Let’s open up those blinds

But someone has to sweep the floor

Pick up her dirty clothes

That job’s not mine

Reflecting on what has happened, Peter also tries to explain what he’s been through, and why he stayed.

Well you can come inside

Wake

Unlock the door, take off your shoes

But this might take all night

To explain to you I would have walked out those sliding doors

But the timing never seemed right

There comes a glimpse of hope in the end of the song, suggesting that peter is willing to open up.

I want to bust down the door

Wake

If you’re willing to forgive

I’ve got the keys, I’m letting people in

The album ends with Epilogue, which has the same creepy nursery music vibe. It ends the story with Peter’s reflection on the past. We learn that some time has passed, has been laid off from his job as a hospice worker, but his dreams are still haunted by Sylvia.

In a nightmare, I am falling from the ceiling into bed beside you

You’re asleep, I’m screaming, shoving you to try to wake you up

And like before, you’ve got no interest in the life you live when you’re awake

Your dreams still follow storylines like fictions you would makeYou’re screaming

Epilogue

And cursing

And angry

And hurting me

And then smiling

And crying

Apologizing

The circle of abuse continues in his nightmares

It’s.. not a happy ending.

Humans like to judge, it makes us feel better about ourselves to take the higher ground and generally, feel smarter than everyone else. I am guilty of that too, I like passing judgements. Hospice cuts so deep for me because I can’t blame anyone. It’s usually suffering that lies beneath our most destructive behavior and Sylvia has suffered a lot. As a kid, and then as a young adult fighting with bone cancer. Her short painful life does not justify her hurting and abusing other people, of course, but I can’t in good conscience claim that I could have handled the situation with more grace than her. There is no salvation for Sylvia. No redemption. She didn’t have time for that. It’s a gray situation where I find myself sympathizing with both characters. And gray situations are always uncomfortable.

The Australian singer and songwriter Nick Cave says “ the common agent that binds us all together is loss” and this, in my opinion, is what the album is about. Feeling the impending doom of loss, facing it, being consumed by it. It resonates with many people, me included, because it deals with grief and loss in the rawest form. The loss of a child, the loss of a life, the loss of a loved one. A love doomed to end in sadness because it was between a very fragile and vulnerable young woman who knew nothing but pain in her very short life and a young man with a savior complex. We collect countless losses through our lifetime, Nick Cave writes, and Hospice story reminds me of mine. Of everything that just couldn’t be saved, of myself reaching for something beyond reach. The loss of a friend. The loss of a family member. The loss of a dream – or was it an illusion?. Sometimes I’m Sylvia, taking out my pain on those who love me, waiting for them to save me. And sometimes I’m Peter, desperately wanting to make things right, consumed and paralyzed by guilt.

I mentioned that wake is my favorite song of the album and it also contains one of the most important lines and messages of the whole piece. Towards the end of song, Peter whispers to himself:

Don’t be scared to speak

Wake

Don’t speak with someone’s tooth

Don’t bargain when you’re weak

Don’t take that sharp abuse

Some patients can’t be saved

But that burden’s not on you

I think you could just replace patient with people.

And then this line echoes, over and overs as the music reaches its peak:

Don’t ever let anyone tell you you deserve that

Wake

Don’t ever let anyone tell you you deserve that

Don’t ever let anyone tell you you deserve that

Don’t ever let anyone tell you you deserve that

Don’t ever let anyone tell you you deserve that

Don’t ever let anyone tell you you deserve that

Don’t ever let anyone tell you you deserve that

Don’t ever let anyone tell you you deserve that

And that’s a powerful line, this. I wonder who’s he talking to. Is he talking to himself, freeing himself from the crippling guilt? Is he talking to Sylvia’s ghost? Does he want to tell her that she didnt deserve to live this short, painful life?

But to be honest, sometimes, when I’m at my lowest point and in my darkes night, I like to listen to this song and think “he’s talking to me”.

As I begin to write this, my heart beats faster and I cannot recognize what’s this hesitating feeling I have. It should be understandable the using of medicine to heal some inconvenient aspects of your body but the guilt I feel comes with the memory of my not so understandable reasons.

So here comes a confession shaped as an assignment: I started getting medicine to be able to stop crying. And because crying means to be weak, then to have to take medicine to stop doing so makes me the weakest of all.

But what I learned researching on my body is that it could feel very freeing to be weak.

Research in art history and art theory has so far dealt with crying rather marginally. We want to research and compile theoretical and historical key texts, significant terms and terminologies, suitable methods also from other disciplines and already existing artistic works/practices on this topic in art history and contemporary art.

And we want to set ourselves up with the development of workshops, mediation tools, manuals, services, coaching, maybe products in a way that we could become operational as an institute and crying experts.

Because: “Sharpen your tears, it is going to be a long one.”*

Mit dem “Crying” hat sich die kunsthistorische und kunsttheoretische Forschung bislang eher marginal beschäftigt. Wir wollen theoretische und historische Schlüsseltexte, signifikante Begriffe und Terminologien, taugliche Methoden auch anderer Disziplinen und bereits existierende künstlerische Arbeiten/Praktiken zu diesem Thema in der Kunstgeschichte und in der zeitgenössischen Kunst recherchieren und zusammentragen.

Und wir wollen uns mit der Entwicklung von Workshops, Mediationstools, Manuals, Dienstleistungen, Coachings, vielleicht auch von Produkten so aufstellen, dass wir als Institut und Crying-Expert*innen einsatzfähig werden könnten.

Denn: “Sharpen your tears, it is going to be a long one.”*

* Nadja Kracunovic 2021: Voicing displeasure #2 The Professional Cry >>