By Xiuyi Wu and Yumiko Mita

Crying Culture in CHINA

In China, crying in front of others has generally been seen as shameful. East Asian society as a whole, including Chinese culture, prefers implicitly expressed emotions. However, many people in China view crying as a privilege for women because there are some circumstances in which it is understandable. This phenomena may then be thoroughly examined, and we will discover

that this exemption does not represent preferential treatment for women.

哭嫁 (Crying Marriage):

Crying marriage is an ancient Chinese wedding custom, now common in some remote areas of rural southern China, in which the bride performs a ritual crying at the time of her wedding. Depending on regional customs, crying usually begins about a month before the wedding, when the bride begins to cry and friends and relatives will weep along with her. It is said that the bride is considered unlucky and even condemned by the public if she does not cry.

Lyrics in Crying: The Sadness of Separation

In some rural communities, a married daughter is compared to spilled water, and it is shameful for her to go back to her mother’s family after her marriage. Therefore, once these ladies get married, it is quite difficult for them to see their parents, relatives, and childhood friends.

Complaint against Marriage

In the past, women did not have enough liberty to choose their spouses, and a lot of marriages were arranged by the parents of the bride and groom. It was incredibly frightening to get married to someone you had never met, so it was crucial to express displeasure with this convention and complaints against society in the lyrics of Cry.

Overview

East Asian social anthropologist Choi Kilsong writes in his book, Cultural Anthropology of Crying (哭きの文化人類学), that Hakka (,客家, Chinese ethnic group) women are largely uneducated and that Hakka society is utterly patriarchal and male-centered. It is stated that women only cry to show their emotions on the seldom occasions of weddings and funerals, and that this was the only occasion where they had the freedom to express their emotions. At village gatherings, women are not allowed to speak. Even when elder women speak up, their opinions are rarely taken seriously.

Freedom to cry

Although most developed regions of China have abandoned this tradition, women have always faced varied degrees of inequality in both life and the workplace due to patriarchal society. Whether being forced to cry, or having the privilege of crying because it is seen as vulnerable are something Chinese women want to have.

Crying Culture in JAPAN

Data from the International Study on Adult Crying suggest that, of the 37 nationalities polled, the Japanese are among the least likely to cry. (Americans, by contrast, are among the most likely.)

“Hiding one’s anger and sadness is considered a virtue in Japanese culture,” a Japanese psychiatrist told the newspaper Chunichi Shimbun in 2013.

涙活 (Rui-Katsu):

It’s safe to say we all have much to cry about these days. People are encouraging one another to express mental distress: Even leaders are crying in public. And that’s OK: Crying can be really, really good for you. And that’s the message that Hidefumi Yoshida, a self-described tears teacher, is out to share. He holds workshops across Japan, where he helps grown-ups learn to cry. Whether it’s breaking the stigma around crying out of grief or simply learning to weep for better mental health, it’s a lesson we all could probably embrace a little more right now.

E.g. The Man Teaching Japan to Cry

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ih1l-FR508o&ab_channel=BBCReel

Culturally Appropriate Crying: Gatherings

When one person starts crying, it is a cue for others to cry. This may be due to peer pressure, or to practice homogeneity. People are usually expected to cry when there is a celebration (e.g. Birthday) with alcohol, or when there is a touching moment (e.g. baseball event).

“Cry-Baby”

Women are expected to cry more than men. The gender stereotype that Japanese women are “cry-babies” and emotional are ingrained. Thus, men expect women to cry at any inconvenience that may arise. This is translated to the anime culture as well.

Overview

● Japanese people are most unlikely to express mental distress

● “Hiding one’s anger and sadness is considered a virtue in Japanese culture”

● Tear teacher, Hidefumi Yoshida, started a movement called “Rui-katsu” (Tear Activity) that encourages people to cry

● While expressing distress or strong emotions are uncommon, Japanese people tend to express their true emotions at gatherings that involve alcohol.

● There are also cultural expectations that when one starts to cry, others join in. Women are expected to cry more than men.

CONCLUSION

● While there are differences, China and Japan are both repressive when it comes to expressing emotions. Therefore, many people suffer from mental health issues.

● Crying could be the best practice to regain health, balance in life, especially when our lifestyles have vastly changed and become limited during COVID-19.

● Letting out emotions should not be a taboo; rather encouraged. People should be free to express themselves regardless of societal pressure.

People go through many rites of passage in their lives. There are customs, weddings, funerals, ancestral rites, and various ceremonies, but each rite has its own procedure. Procedures consist of actions that add meaning to the ceremony or put the participants’ minds into it. These actions are often symbolic, and the clothes and tools used during the rites show that they contain human origins.

Funeral rites are the last ceremonies a person performs. What is different from other rituals is that the main person becomes an object, not a subject. The dead cannot drink or sing. He can’t dance and he can’t cry. You can’t do anything about consciousness for yourself. Therefore, it is safe to say that funeral rites are the rituals of the remaining people.

A bier is a tool used to enshrine the dead to the burial site in the process of holding a funeral ceremony. It is a palanquin on the way from this world to the next world. It is an expression of the sad will of the remaining people who have not been able to fulfill their promise to burn a palanquin on the road to the underworld. Like this, the bier has many decorations.

Depending on circumstances, the sangju may raise the bier to the second or third floor and make it in the shape of a pavilion. At the top of the bier, a ridge was raised with blue and yellow dragons. In the center of the ridge of the ridge, a figure riding Haetae was made and decorated. Dongbangsak is a grim reaper and is said to play a role in enshrining the dead in a good place. Kkokdu, Dongja, Dongja, servants, and maids were placed on the top of the ridge. Birds of paradise, phoenixes, and goblins were also drawn. They protect the dead from evil spirits and assist the dead on their way.

There are musicians who play musical instruments and Gwandae Kkokdu who perform tricks. Akgong is a model holding a daegeum, gaegwari, sogo, nabal, and bara. Gwandae Kkokdu is a model of a person who is a talented person who performs somersaults or makes people laugh with humorous movements and takes charge of traditional music or sings. In addition to the figures, there are also animal puppets. It is a bird or an animal, and the chicken is a role in chasing evil spirits because it announces the dawn, and the chicken crest symbolizes the crest.

Bonuses have a series of matrices. Mr. Bang Sang (方相氏) drives out the ghosts from the front and guides Young-gu. Next is Myeongjeong (銘旌), a flag on which the rank, official position, and surname of the deceased are recorded in white letters on a dark red background. Next, Yeong-yeo, a palanquin that enshrines the soul, follows, followed by a chuk-gwan (祝官) who reads a congratulatory message holding a gong (功布). Horror is the burlap cloth that is used to wipe the coffin when it is buried. The bier follows, and the shovels go side by side on the left and right. The shovel is a fan made of wood, containing the wish to guide the soul of the dead to a good place.

“If I go now, when will it come?

(they collectively sing together and it seems like a crying sound)

On the way to Bukmangsancheon, leave all your lingering feelings behind and go, uhhh~ Deheya”

The sound of the bier is sung by the yoreungjap (catfish sound), and the bier bearer responds with a chorus (sound behind the scenes). The lyrics were not fixed, so they improvised and sang according to the deceased.

The bier repeats going and standing. When they meet the bridge, they stop again, the sender cannot bear to let go, and the departing dead cannot bear to leave.

Sometimes I feel the emotions of things.

Those objects do not speak to humans, but their presence gives me a certain feeling. The invisible story of how things are used and discarded in human society can be understood just by being near them. Every time I pass the pottery tomb, where abandoned pottery is buried, I can sense the emotions of the broken pottery. Perhaps, it’s because I can identify with them at some point. They don’t cry out loud. They just remain there silently and are buried with time. To me, the act of crying is not necessarily the fact that water comes out of the body and the body trembles. Every day, just existing, endures the weight of life and embraces all kinds of emotions. The pottery, formed from clay and eventually discarded after it has run out of life, returns to clay again and repeats itself infinitely. In the same time as eternity, I silently look at the clay lumps, crying, and the vessels that are losing their original shape.

I used the broken bowls to serve food and give them a new purpose, hoping to breathe new life into them for a while. These are also human-oriented emotions and actions, but through this, I try to project and heal myself by connecting to those objects, even a little bit.

why do we cry?

why are we looking up images of crying?

…..cry, cry, cry……

…..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry……

…..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry……

…..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry……

…..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry……

…..cry, cry, cry……and cry again.

A song, a broken heart and a river of tears – by Emily Grawitter

Cry Me a River

Now you say you’re lonely

You cry the whole night thorough

Well, you can cry me a river, cry me a river

I cried a river over you

Now you say you’re sorry

For bein’ so untrue

Well, you can cry me a river, cry me a river

I cried a river over you

You drove me, nearly drove me out of my head

While you never shed a tear

Remember, I remember all that you said

Told me love was too plebeian

Told me you were through with me and

Now you say you love me

Well, just to prove you do

Come on and cry me a river, cry me a river

I cried a river over you

I cried a river over you

I cried a river over you

I cried a river over you

When i listen to music from the 50s or 60s there is many tears, lovers, crying and feelings of loss involved.

The song „Cry Me a River“ (written by Arthur Hamilton in 1953, and sung by Julie London later on) seems to be one of the most popular songs connected to crying. I have always adored the original version. Not because it is specifically sad or makes the listener cry, but the feeling of: „I was hurting, because you made me cry. Now it is your turn to show me that you really love me.“

There is something extremely toxic in the need to make each other cry, just to prove the love to each other. But i have always felt, when Julie sings it, she does it with such soothing and honesty, that you would do anything to shed a tear for her. Using tears to prove something, does make a lot of sense. To express extreme sadness, pain or emotion, tears are the ultimate „tool“. When there are tears, it is serious. Your inner feelings are shown to the outside world. So i think the term of „Crying a River“ is that popular, because crying as itself is so pure and emotional, that a whole river of tears, would not only be very emotional, but also very unrealistic and impossible to achieve. And in the end there could be two outcomes to this. Either the lover is able to achieve the goal of crying so much, that she takes him back, or, she already knows he wouldn’t be capable of crying a river and there is no realistic way, that she will take him back. What better way to know someone loves you, if they do the impossible for you?

This is not my personal opinion, but that is what i think Arthur Hamilton and Julie London wanted to get across. I felt like i had to analyze the song title a little, because it just screamed (or cried) at me when i listened to it.

You can listen to the song here:

Text von Emily Grawitter

Ein Gruppenexperiment mit Jan Munske, Lina Unger und Hannah Röbisch

Der Name „Klageweiber“, so extrem er auch klingen mag, lief mir erst vor einem Monat über den Weg. Gemeint sind damit Frauen, die auf Trauerfeiern und Bestattungen gegen Bezahlung die Toten beklagen, besingen; ja sogar beschreien. Das Klagen von Klageweibern lässt sich zurückverfolgen bis ins alte Ägypten (3000 v. Chr. bis 395 n. Chr. ) und Babylonien (1800 v. chr. bis 1595 v. Chr.) (vgl. Stubbe, Hannes: Formen der Trauer, Berlin, Dietrich Reimer Verlag Berlin, 1985). Damals war es üblich, dass Scharen von klagenden Menschen, hauptsächlich Frauen, an Trauerzügen teilnahmen (auch Männer gab es sicher, Aufzeichnungen belegen dies aber nicht). Dabei wurde lauthals nach außen geklagt, in aller Öffentlichkeit, ohne Scham und ohne Hemmungen. Heute gibt es noch vereinzelt in sizilianischen Bergdörfern oder kleinen Orten in Rumänien die Kultur der Klageweiber, jedoch sinkt die Nachfrage und auch der Beruf ist nicht mehr verbreitet.

Eine Frage, die sich mir mit der Auseinandersetzung allerdings am häufigsten stellte, war: Weshalb um eine fremde Person klagen? Warum sich immer wieder mit Trauer konfrontieren und immer wieder Angehörigen beim Leiden zusehen? Innerhalb unserer Projektgruppe beschlossen wir also, ein Experiment zu machen und dem nachzugehen. Wir besuchten die Trauerfeier einer fremden Person. Ohne persönliche Informationen zu kennen, aber natürlich mit der Absicherung, dass es eine öffentliche Trauerfeier wäre, die es uns gestattet teilzunehmen. Wichtig war uns dabei, die Teilnehmenden weder zu stören, noch in die Trauerfeier einzugreifen oder auf uns aufmerksam zu machen, denn Fremde auf einer Trauerfeier kommen nicht so oft vor.

Wir wussten nicht, was uns erwartet, stellten uns aber auf einen bedrückenden Tag ein. In einer kalten Kirche sitzend, schwarz gekleidet, traurige Lieder singend und Menschen leidend sehen. In einer kalten Kirche saßen wir zwar wirklich, doch das (in unserem Fall) stille Beklagen einer fremden Person fühlte sich nicht so bedrückend an, wie wir dachten. Als „rührend“ würde ich es eher bezeichnen. Wir hörten der Predigt zu, der Lebensgeschichte eines Menschen, den wir niemals gekannt haben und ich selbst ertappte mich beim Schmunzeln, als ein selbstkomponiertes lustiges Lied der verstorbenen Person abgespielt wurde. Und auch beim Liedersingen entwickelte sich mein unsicheres Mitmurmeln zu einem normal lauten Gesang, der mit dem aller Anderen mitschwang.

Erst als ich beim letzten Lied und dem damit verbundenen „Totenzug“ hinausging und einen Blick auf die trauernden Angehörigen erhaschte, bekam ich einen Kloß im Hals. Ich konnte leises Schluchzen hören und sehen, wie sich Menschen in den Armen hielten. Andere gingen mit gesenktem Kopf, eine Scham des Weinens? Der Zug entfernte sich und wir verließen die Kirche, weg von der trauernden Menschengruppe, nachdenklich.

Etwas hatte sich verändert. Ich glaube es war gut, dort gewesen zu sein. Im Gegensatz zu Klageweibern zwar eine stille Anteilnahme, aber trotzdem: Anteilnahme. Wir waren da und haben uns von einem Menschen verabschiedet und ihn be“weint“. Selbst könnte ich das wohl nicht regelmässig machen. Aber ich habe das Gefühl, nun etwas mehr zu verstehen, worum es beim Klagen um eine mir unbekannte Person geht.

Quellen:

Stubbe, Hannes: Formen der Trauer, Berlin, Dietrich Reimer Verlag Berlin, 1985

Barbu, Mircea: Der Tod ist ihr Hobby: Die Frauen, die auf fremden Beerdigungen weinen, 03.09.2019, https://www.vice.com/de/article/bjqbxq/der-tod-ist-ihr-hobby-die-frauen-die-auf-fremden-beerdigungen-weinen

NewFinance Redaktion: Die Tradition lebt: Die letzten Klageweiber in Rumänien, 08.04.2021, https://magazin.dela.de/die-tradition-lebt-die-letzten-klageweiber-in-rumaenien/

Hucal, Sarah: Professionelles Trauern – ein altes Ritual in Griechenland, 15.11.2020, https://www.dw.com/de/volkstrauertag-frauen-trauern-griechenland-klageweiber-moirologie/a-55590388

EmmaLife: Totenkulte | Ägypten: Klageweiber und muslimische Trauerrituale, 28.07.2021, https://blog.emmalife.ch/totenkulte-aegypten-klageweiber-und-muslimische-trauerrituale

Book recommendation:

James Elkins: Pictures and Tears. A History of People Who Have Cried in Front of Paintings, Routledge, 2001, https://jameselkins.com/pictures-and-tears/.

Book has two parts:

Art

The first part deals with the works of Sargent, Regnault, Picasso, Rothko and others on their history and importance and examines the states of people who cried in front of a painting. How to make the audience cry and whether education and familiarity with art have an effect on crying or not

Tears

The second part begins with an overview of the opinions of thinkers on crying. And then it shows how in the contemporary world shedding tears in front of a work of art has become a wrong thing. The specific audience considers the art of shedding tears as a form of weakness, or is so caught up in the history of the work that it is meaningless for them to see passion. Elkins says that he has suffered from the same problem and his understanding of art history does not allow him to fully face the work. This thinking has also expanded to the general audience and it seems that art should be viewed without much excitement.

Interestingly, most of the academics who had a tearful memory asked not to be named.

This is a piece of art “The moon in the forest” I made during my depression, a vision from my dreams. At that time, the psychiatrist asked me to describe my feeling. I felt like a heavy black gas enveloped me. I recorded this feeling in the form of electronic painting. Whenever I see this painting now, I can still recall the feeling at that time, which may be the ability of art to record emotions.

In the artwork, I added a character, looking for light in the dark forest, I hope to remind people who are suffering from depression in this way, never give up looking for light.

CW: mental health, suicide, self-harm

地雷系 Jirai Kei is a fashion trend that gained popularity on social media platforms like TikTok around 2019/2020.

It literally translates to „landmine-type”, stemming from the from phrase 地雷を踏んだ (“I stepped on a landmine”). It is also a Japanese slang term for “trigger” and describes a person that is easily triggered over minor events, keeps exploding with abusive behaviour, which makes interacting with them as if you’re walking around a minefield.

Stylistically, people who dress in Jirai fashion place a heavy focus on their eye make-up, with the goal to exaggerate their eyes to simulate the teary state of the pleading emoji. By applying red and pink eyeshadow to the under-eye area, using downturned black eyeliner and brown contacts to make the eyes look bigger, it creates a look as if the person is always near tears or cried already.

While there is definitely nothing wrong with having a distinct fashion style, one that in this case can be best described as “dark but cute” with its mostly black and pink colour palette, the public

image towards the Jirai Kei aesthetic in some areas of Japan is extremely negative because the fashion originated in Kabukicho. The entertainment district in Shinjuku, Tokyo, is mostly known

for its many host-, hostess-, nightclubs and love hotels. In the last years it also became a temporary home for many toyoko kids (teen runaways), whose behaviour is highly associated with binge drinking, heavy partying, self-harm, suicide, sex work and other “shocking” or

“rebellious” behaviour.

Therefore, at least in Japan, Jirai Kei as a fashion style is hard to separate from the lifestyle, due to the prevalence of overlap between the two. And there are sadly arguments for the trendiness of Jirai Kei contributing to real life consequences, such as increased rates of self-harm amongst teens. However, this cannot be seen as an isolated phenomenon and reveals more about the still silent treatment surrounding mental health and the ongoing lack regarding awareness and support of those who suffer from it in huge parts of Japanese society.

I thus find it very fitting that a part of the population who is desperately in need of help but seems to be disregarded as just going through a “rebellious phase” look like they are constantly on the verge of crying.

@yume.chii on Instagram

Public performance, Chemnitz, Jan, 2022

Rand Ibrahim

Photography: Leila Keivan

Could a person carry all the grief in the world?

Is that an exaggeration? An overrated dramatic scene?

One day you read in the news: a gang of rats ate an infant’s face

Then you look to the corner of the street and you see a child kicking a dog until he breaks every little rip in his chest.

“Women are still raped and dumped in trash containers”.

On another day, you can extract colorful fragments out of the belly of a smelly dead fish with rotten eyes, which was in the market for people to buy and eat.

There are many reasons to make you cry and burden you with grief and sorrow, not to mention the personal ones.

Sensitivity is a problem

Where did I learn that from?…

When did I learn that?

Photography: Leila Keivan

You were born sensitive; spend your first years crying over anything that does not suit your moody existence.

Your sensitivity contracts while you observe the behaviour of the maniac adults around you.

Your little size friends in school, those who were trained better

will make you realise you should preserve and keep your tears to yourself, just in case you want to survive the next day.

This time a kid will hit me and I will not cry,

I will hit back.

This time they will bomb us,

I will not cry.

I will survive.

It keeps going on until you understand, your tears are valuable, you should only shed them when it is necessary. I will save my tears for the worthy but I am thirty-years old now, and my tears cannot stop running metaphorically.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1pxxmYGqEmFICI2XI5GPL8GKErZY9168m/view?usp=sharing

Due to current events, there has been a huge increase of public interest in face mask and tear collection supplies.

Some countries, made the use of an TCFP (Tear Collection Face Piece) mandatory in most public areas to combat the spread of new, more transmissible variations of emotional and emphatic behaviour.

What is an TCFP mask?

Firstly, the TCFP is actually classed as a collecting vessel, rather than a mask, meaning they offer better collecting capacity. TCFP stands for “Tear Collection Face Piece”, with the number corresponding to the level of collecting capacity the piece provides, 1 being the lowest level of tears collecting capacity and 3 being the highest.

5 key benefits of using an TCFP mask

1)At least 94% collection of all fluids that are emissed during crying

2)Two way direction, protecting the wearer and others

3)Higher fluid resistance against salty tears

4)Better visual hide of the emotional status of the wearer

5)Made with breathable filtering layers

On Cry Baby by Roger Waters, 1990

Content and Context

The 85-minute-long 1990 film Cry Baby by Roger Waters is a parody on the musical film and an exaggerated love story between two teenagers from opposing groups: the “Squares” and the rebellious “Drapes”. Johnny Depp plays the leading role, other actors include Amy Locane, Iggy Pop, Traci Lords and Patty Hearst. A box office failure during its initial release, the film has subsequently become a cult classic.

Crying is a common thread throughout the film and marks different emotional states of its main characters. Moreover, crying and tears take on a symbolic meaning during the film and refer to memories and experiences of the film characters.

Focus 1 – Tears in the Musical Film

The genre of the musical film emerged in the early 1920s in Hollywood, USA. In a musical film, dance and song interrupt the film plot and address dreams, visions of the future, comment on what is happening in the film, or bring up the non-obvious. Mostly they reflected the ideals of the “American way of life” with stereotypical gender portrayals and the ideal-typical everyday life of the American middle class. In the 1970s, this changed and the claim to come closer to reality became palpable.

For the film musical, new recording techniques were invented at the beginning of the 1930s, which were intended to free the viewer from the perspective of the theater spectator: in the so-called “overhead shots,” hundreds of dancers formed human ornaments for the singers.

Focus 2 – Tears as Film Material

In a film production, the teary eyes of a performer are produced with different means. There are the natural tears the actor creates by concentrating and getting into the role, but there are also special compounds that are applied to the eye and create artificial tears.

Tear stick – is a substance which is applied to the eye lower limbs. Due to the menthol content, the eyes start tearing within a very short time.

Tear blower – is a preparation that also contains menthol, but is dusted directly into the eyes.

Eye drops – are sterile eye drops that are put into the eye and then flow out again. However, the effect lasts only a few seconds.

Vaseline product – is a petroleum jelly based product that works like a mask and allows for a “standing” tear.

Focus 3 – Tears as a Tattoo in Prison

Originally, the “stick and poke” style tear tattoo was applied below the eye to represent the shedding of a tear. The tear tattoo is a symbol that has negative connotations, as it is most often associated with gangs and criminal activity. For example, it can denote a stay in a prison, it can denote that the the owner of the tear tattoo killed someone, it can denote that a good friend of him/her was murdered, or it can denote that the owner of the tear tattoo was forced to get the tattoo in prison. Multiple tears tattooed under the eye can represent multiple people the owner of the tear tattoo killed or the number of years spent in prison. Sometimes each tear represents one person murdered or one year in prison, in other cases each tear may represent 10 or 20 people or years. Since there is not necessarily remorse for these crimes, the tear becomes an ironic symbol, as a tear usually expresses sadness. It is a common misconception that the owner of a tear tattoo is sad about something, since in fact he/she is very proud of what the tears represent.

Sources

https://www.br-online.de/jugend/izi/deutsch/publikation/televizion/24_2011_1/Mikos-Wenn_die_Traenen_fliessen.pdf

https://www.businessinsider.com/how-makeup-artists-help-actors-cry-2018-5

Bruun Vaage, Margrethe: Empathie. Zur episodischen Struktur der Teilhabe am Spielfilm. In: Mon-tage/AV, 16/2007/1, S. 101-120.

Altman, Rick (1981): Genre: The Musical. London/Boston: Routledge&Kegan Paul.

https://www.tattooseo.com/teardrop-tattoo-meaning/

Porcelain objects in liquid morpho-logic, 2023

The limb of my tongue is drowning in a melting vessel

But I can’t be seep

So I’m heating my breath and it freezes in the air into hard snowflakes bitter as knives

The vase is melting as well as the vessel as well as a tongue as well as a mother as fast as I was gone so far as I was told as must as we have to from vessel to shore from here to the tip of the speech. Your timbre and sounds are only formal data in a guest communicative environment. Your fracture angles are not read as signs, they rise into the air in the logic of body inertia, but without reaching other vessels they freeze, caught unawares by the lack of atmosphere for their reception. They fall back into your body. Ukrainians are scattered around the world like so many other refugees. Loneliness in the experience of trauma, social isolation is transformed into physical pain from the impossibility of mutual fluctuation in the usual modus bodily use of the Mother tongue. Language is a technology, an artificial extension of the body, a cyber-limb of the psyche, especially perceptible in situations where it can’t be used. A tongue, this vessel, the Matrixial Borderspace as a misty suspension where drops hanging in the air effectively commiserate, even if the prototype of this kind of relationship is the prelinguistic state of the infant. This nourishing suspension suspends the question of what exactly is language, how virtual the verbal is and how much it is projected into the flesh of body and routine motility, whether the eyelashes are involved in the act of speech or maybe invisible muscular impulses of the internal organs.

Judith Butler photographed by Bracha Ettinger in Berlin, IPA Conference, 2007

“Eurydice is, as we know, already lost, already gone, already dead, and yet, at the moment in which our gaze apprehends her, she is there, there for the instant in which she is there. And the gaze by which she is apprehended is the gaze through which she is banished. Our gaze pushes her back to death, since we are prohibited from looking, and we know that by looking, we will lose her. And we will not lose her for the first time, but we will lose her again, and it will be by virtue of our own gaze that she will be lost to us, and that she will, as a result, be apprehensible only as loss.

So it is not just that she is lost, and we discover her again to be lost, but that in the very act of seeing, we lose.”

(Judith Butler 2004: Bracha’s Eurydice)

Bracha Ettinger, Water-Dream Artistbook (Notebook, 25×25 cm), 2011

Menschen weinen als Reaktion auf eine Krise, die das eigene Körpersystem verwirrt und zerrüttet. Ein Prozess des Druckablasses und die Suche nach Sicherheit und Halt wird durch den verletzlichen Organismus eingeleitet. Genauer beginnt die fleischliche Oberfläche zu bröckeln, damit die Tränen die zarten emotionalen Samen des Menschen bewässern können. Eine Pflanzen-Menschen-Hybrid-Metaphorik baut sich auf, die nicht von ungefähr kommt. Schließlich scheint das rhetorische Potenzial enorm, das Tränen der Pflanzen im Prozess der Guttation zu erkennen.

Guttation ist ein Notfallmechanismus von Pflanzen, die sich in Lebensräumen aufhalten, wo eine zu starke Luftfeuchtigkeit vorherrscht, sodass es unmöglich ist, zu transpirieren. Somit kann der Vorgang – zum Weinen analog – als Krisenschutzhebel verstanden werden, der statt Wasserdampf Wasser durch die Blattenden absondert. Dieses Wasser perlt in Tropfenform vom Blatt wie die Träne über die Wange. Die Guttation scheint auch seinen Namen von dieser Erscheinung zu haben, da es sich vom französischen „la goutte“, zu Deutsch „der Tropfen“, ableitet.

Das, was in Tropfenform ausgeschieden wird, nennt sich Xylemsaft. Bei diesem handelt es sich um Guttationsflüssigkeit bestehend aus Phytohormonen, die in Wasser gelöst von den Wurzeln über den Spross durch die Hydathoden an den Blättern herausgedrückt werden. Phytohormone werden auch umgangssprachlich „Pflanzenhormone“ genannt und sind wie beim Menschen für die Regulierung der Entwicklung und des Wachstums der Pflanze zuständig. Nennenswerte Beispiel hierfür sind Florigen oder Cytokinin. Bei den Hydathoden handelt es sich um Wasserspalten, über die die Guttationsflüssigkeit durch Wurzeldruck an die Umwelt abgegeben wird, um den Wasserstrom und Mineralienaustausch aufrechtzuerhalten.

Folglich kann die Guttation als Kompensationsstrategie mancher Pflanzen begriffen werden, die mit sich führt, von einem inneren Druck geformte „Tränen“ nach außen zu pressen, wenn die Umgebung eine luftüberfeuchte Krisensituation herbeiführt (anders zu den von außen gebildeten Tautropfen). Neben den physischen Analogien, die zwischen menschlichen und pflanzlichen Tränen möglich sind herzustellen, wie z.B. die Tropfenform oder die Ausscheidung in Wasser gelöster Salze und Mineralien, eignen sich metaphorische Parallelen besser für die eigene

CRYING REFLECTION.

So wie wir schnell Gesichter in bestimmten Strukturen erkennen, äußern wir scheinbar schnell unsere Vermutung, dass das Tropfen eines Wesens oder gar einer Sache an den Prozess des Tränens erinnert. Unsere empathische Fähigkeit motiviert diesen Vergleich, da wir nicht wirklich schätzen, was tatsächlich der Grund für das bildähnliche Tränen von Hundeaugen oder das Harzen von Baumrinde sein soll, sondern unseren eigenen Moment des Weinens darin sehen. Vielleicht gerade, weil wir keine genaue Antwort darauf haben, warum wir manchmal weinen. Dabei kommt der Gedanke auf, dass durch die Guttation eine simple, aber wesentliche Begründung geboten wird. Es geht hierbei um die Aufrechterhaltung des verletzlichen Systems einer zum Überleben getriebenen Lebewesen – ob Pflanze oder Mensch. Gerade im Moment des Zusammenbruchs können Tränen helfen, den Druck aus dem inneren mit dem Druck von außen wieder in Balance zu bringen bis man aufhört, Salzwasser auszustoßen, um nicht auszutrocknen.

Ein Tränenkreislauf wird hergestellt.

Der zyklische Ablass und Aufnahme von Druck soll (scheinbar im Sinne eigener poetischer Ansprüche) als Ventil dienen, das Wasser, wie den Xylemsaft, nicht zu eliminieren, sondern erst als flüssige Tropfen abzugeben, die verdampfen, um folglich ein weiteren Organismus in den Zustand des reinigenden Weinens zu bringen. Wiederum erhöht sich der Wassergehalt in dessen Umgebungsraum. Der Wasserdampf wird absorbiert und kann das Überlaufen des Körpers mit Tränen erneut begünstigen. Tränen werden zu Tränendampf und der Kreislauf wird fortgefahren. Zusammen im selben Raum zu sein, der durch eigenes Weinen luftfeuchter wird, stellt einen eigens bezeichneten „Pumpraum der Katharsis“ dar, in dem sich die Wesen im Mit- oder Gegeneinander anweinen.

A short story and performative reading by Camilo Londoño Hernández

[Spanish]

[Al final todos muertos]

Te matarán. Me matarán. Nos matarán. Me matarás. Me mataste. Os mataréis. Los mataron. Por hijueputas. Por maricas. Por pendejos. Por guerrillos. Por paracos. Por pendejos. Por maricas. Por campesinos. Por ciudadanos. Al final…¡Todos muertos!

Iba vestido de azul oscuro. El buzo y el jean monocromáticos parecían una sola prenda casi un overol de obrero en turno de domingo. Cuando el vidrio del bus le dio reflejo a su rostro se sintió como un cursi poema.

No podía arreglarlo. Tres de la tarde.

Jairo, Jota, su amigo, el muerto, se estaría descomponiendo mientras él pensaba en la mejor ropa que podía llevar a un velorio. Aunque era cierto, su cita no era con Jota; lo que lo esperaba era tan sólo eso: el cuerpo. El cuerpo sudoroso, bañado, agasajado, estirado, moribundo, petrificado, exaltado, muerto, agrio, frío, tibio, cercano, triste, ajeno, en llanto, vacío. El cuerpo de Jairo y los dedos extrañamente redondeados por las uñas, con los nudillos lisos y los huesos gordos, pesados. La columna y esa cicatriz en la espalda baja, como mirando sobre sí, hacia la carne.

-Es de una cirugía.

-¿Hace mucho?

-De niño. No nos conocíamos.

Eso es lo que iba a ver. El cuerpo de su amigo, Jairo, su amante. Las rodillas sucias, los hombros en triángulo, la barriga ancha, los ojos para adentro, tranquilos, pesados, muertos sobre su cuerpo.

Eran la tres de la tarde. Jairo Fernández. Sala 6.

Esculcó el cementerio con la mirada y se adentró en el laberinto de puertas, nombres y ataúdes. Las escalas eran amarillas y las paredes blancas casi grises como huesos en formol. De tanto en tanto, entre las puertas o por los pasillos, pasaban negras manchas de gente, y a veces, por error, alguna mujer anciana se movía con una camisa ancha y florida rompiendo el ritmo solemne de los cuartos de velación.

Sala 6.

A pesar de de ser un espacio pequeño, en ese cuarto se podían encontrar todas las personas con las que un ser humano se puede cruzar en la vida. Desconocía lo popular que llegaría a ser la muerte de su amigo. Se asombró. Respiró con espantosa esperanza y se zambulló entre la masa como un pequeño cuerpo inmerso en otro más grande. Al detallar el ataúd observó que la ventanita que deja ver el rostro de los muertos estaba cerrada. Intentó abrirla pero no pudo. Del tumulto estallaron voces y llantos con sensación a chisme. Las señoras empezaron los rezos confundiéndolas con anécdotas que no correspondían al novenario.

-¡Pobre Jairito, cómo quedó de desfigurado!

-¡Ay mija, es que ahora no respetan nada!

-¡Qué pesar de ese muchacho, con el cuerpo tan bonito que tenía!

En medio de los murmullos pensó que no sabía cómo fue la muerte de Jota. Una amiga en común había dejado un mensaje entrecortado, entre llantos, en el celular. “¡Jueputa!, Jota, lo mataron, lo mataron, a Jairo, ¡a nuestro Jota!”. Él intentó devolverle la llamada, pero no obtuvo respuesta. Solo un mensaje de texto rápido con el nombre del velatorio y la dirección. Y ahora él estaba ahí, vestido con un mal color azul, mirando una caja sin saber por qué.

“Dos cuchilladas en la espalda para volverle a abrir la cicatriz”. “A él lo torturaron agarrándole el pene con pinzas eléctricas”. “Después de robarle y golpearlo, le metieron un revolver en el culo y al disparar, las tripas se expulsaron por el ombligo”. “¡Para que aprenda por… ¡marica!” Seguro Jairo tendría el ano caliente. Ya no tendría más esa cicatriz.

Rozó el cajón con los dedos y desarmó cualquier imagen que sentía sobre los párpados. Sabía que el cuerpo de Jairo estaba ahí y aunque de él sí recordaba cierto calor en la piel, al tocar la madera del cofre sentía un cuerpo frío, ni si quiera tibio, frío como una nube de lluvia o un dulce en el refrigerador.

Un grito cortó el barullo del salón. La madre, como sostenida por el aire, caminó hacia el féretro mientras la habitación se vaciaba. Él también se movió. Ella gritaba como una fruta e podrida que destila jugos amargos. No hubiese imaginado que la madre de Jota luciera así. Para él, aquella máquina de gritos debía ser una señora más alta, más gorda y con menos llanto sobre la lengua. No importaba. Él también le había mentido a Jairo sobre sus padres.

-Viven en el Caribe. Por eso nunca están en la ciudad.

Sin embargo, aquella mujer resultaba siendo lo más familiar que había visto desde que ingresó al cementerio. Su amiga no estaba. Unos compañeros que pensaba encontrarse, tampoco; y el cuerpo, lo único conocido y memorizado para él, lo que motivaba aquella cita, parecía no estar ahí. “Desafortunado encuentro”, pensó sin poder llorar.

Salió a buscar un café y al regresar leyó en la cartelera que se estiraba sobre la puerta del velatorio: “Jairo Hernández. Sala 6”.

Repasó las letras incrédulo.

Jairo Hernández. Fernández. Hernández. Jairo. Jota. Juego. Jugo. Muerte. Coja. Ardor. Sudor. Amor. Canción. Soledad. Calle. Amor. Aquí huele feo. ¿Quieres caminar? Sigamos por aquí. Me duele. Tengo sueño. Vamos a comer. Esta noche no puedo. La otra semana puede ser.

Quiso bostezar, abrir la boca para simular un grito. Pensó en Jairo y se le cerró la mandíbula con un suspiro. Volvió a repasar la escena tétrica que tenía en frente y se quitó el buzo azul para destapar la imagen de una caricatura fluorescente que se estallaba sobre una camiseta blanca. No intentó buscar la verdadera sala de velación, ni llamar a su amiga, ni redimir su cita con el amor ni la muerte. Salió del cementerio con el suéter sobre los hombros y las mangas vacías rebotándole contra la espalda. Caminó hasta el siguiente parque, donde se sentó a esperar que el sol, cansado del día, se hiciera azul.

***

[English]

THE DATE

[In the end all dead]

They will kill you. They will kill me. They will kill us. You will kill me. You will kill me. You will kill each other. They killed them. For motherfuckers. For faggots. By assholes. By guerrillas. By paramilitaries. By assholes. For faggots. For peasants. In the end… All dead!

He was dressed in dark blue. The monochromatic sweater and jeans looked like a single garment, almost like the overalls of a worker on a Sunday shift. When he saw his face reflected in the bus glass, it felt like a corny poem.

He couldn’t fix it. It was three o’clock in the afternoon.

Jairo, Jota, his friend, the dead man, was decomposing, and he was thinking about the best clothes to wear for a funeral. But his date was not with Jota. What awaited him was just that: the body. The sweaty body, bathed, showered, entertained, stretched, dying, petrified, exalted, dead, sour, cold, lukewarm, close, sad, alien, crying, empty. Jairo’s body and fingers were strangely rounded by nails, with smooth knuckles and fat, heavy bones. The spine and that scar on the lower back, as if it looks over itself, toward the flesh.

-It’s from surgery.

-A long time ago?

-I was a child, and we didn’t know each other yet.

That’s what he went to see: the body of his friend, Jairo. His lover and his dirty knees, his triangular shoulders, his thick belly, his inward eyes, quiet, heavy, dead on his body.

It was three o’clock in the afternoon. Jairo Fernandez. Room 6.

He scanned the cemetery with his eyes and entered the labyrinth of doors, names, and coffins. The stairs were yellow, and the walls were white, almost gray, like bones in formaldehyde. In between the doors and along the corridors, crowds dressed in black walked around. Once in a while, by mistake, one old woman moved in an oversize shirt with flowers breaking the solemn rhythm of the wake rooms.

Room 6.

Despite being a small space, in that room, you could find all of the people that one human being could come across in life. He did not know how popular his friend’s death would become. He was amazed. He breathed with frightened hope and plunged into the mass as a small body immersed in a larger one. As he examined the coffin, he noticed that the little window that normally shows the face of the corpse was closed. He tried to open it but could not. From the tumult burst voices and cries that felt like gossip. The ladies began the prayers, confusing them with anecdotes that did not correspond to the novena.

-Poor Jairito, how disfigured he was!

-Oh, my dear, they don’t respect anything now!

-What a pity about that boy, with the beautiful body he had!

In the middle of the murmurs, he realized he didn’t know how Jota’s death happened. One mutual friend had left a broken message, in tears, on his cell phone. “Fuck! Jota! They killed him, they killed him, they killed him! They killed Jairo, our Jota!” He tried to call her back but got no answer, just a quick text message with the name of the cemetery and the address instead. And now he was there, dressed in an ugly blue, staring at a box without knowing why.

“Two stabs in the back to reopen his scar.” “They tortured him by grabbing his penis with electric pliers.” “After robbing and beating him, they stuck a revolver up his ass and when they fired, the guts were expelled through his belly button.” “So that’s how he learns … faggot!” Surely, Jairo would have a warm anus. He wouldn’t have that scar anymore.

He brushed the drawer with his fingers and erased whatever image he felt on his eyelids. He knew Jairo’s body was there. Although he remembered a certain warmth on his skin when he touched the coffin’s wood, he felt a cold body, not even warm, cold like a rain cloud or a candy bar in the fridge.

A scream cut through the hubbub of the room. The mother, as if held by the air, walked towards the coffin as the room emptied. He also moved. She screamed like a rotten fruit that exudes bitter juices. He would not have imagined that Jota’s mother looked like that. To him, that screaming machine must have been a taller, fatter lady with less crying on her tongue. It didn’t matter. He had lied to Jairo about his parents, too.

-They live in the Caribbean. That’s why they are never in town.

However, that woman was the most familiar thing he had seen since he entered the cemetery. Her friend was not there. And the body, the only thing known and memorized to him, the reason for the meeting, did not seem to be there. “Unfortunate encounter,” he thought without being able to cry.

He went out to get a coffee. When he returned to the room of the wake, he read the sign stretched over the door: “Jairo Hernandez. Room 6”.

He went over the letters in disbelief.

Jairo Hernández. Fernández. Hernández. Jairo. Jota. Game. Juice. Death. Lame. Burning. Sweat. Love. Song. Loneliness. Street. Love. It smells bad in here. Do you want to walk? Let’s go this way. It hurts. I’m sleepy. Let’s eat. I can’t tonight. Maybe next week.

He wanted to yawn to open his mouth and simulate a scream. He thought of Jairo. He closed his jaw with a sigh. He went back over the gloomy scene in front of him and took off his blue sweater. An image of a fluorescent cartoon exploding on a white T-shirt was uncovered. He didn’t try to find the real wake room, call his friend, or attend his date with love and death. He left the cemetery with the sweater over his shoulders and the empty sleeves bouncing against his back. He walked to the next park. There, he sat waiting for the day-weary sun to turn blue.

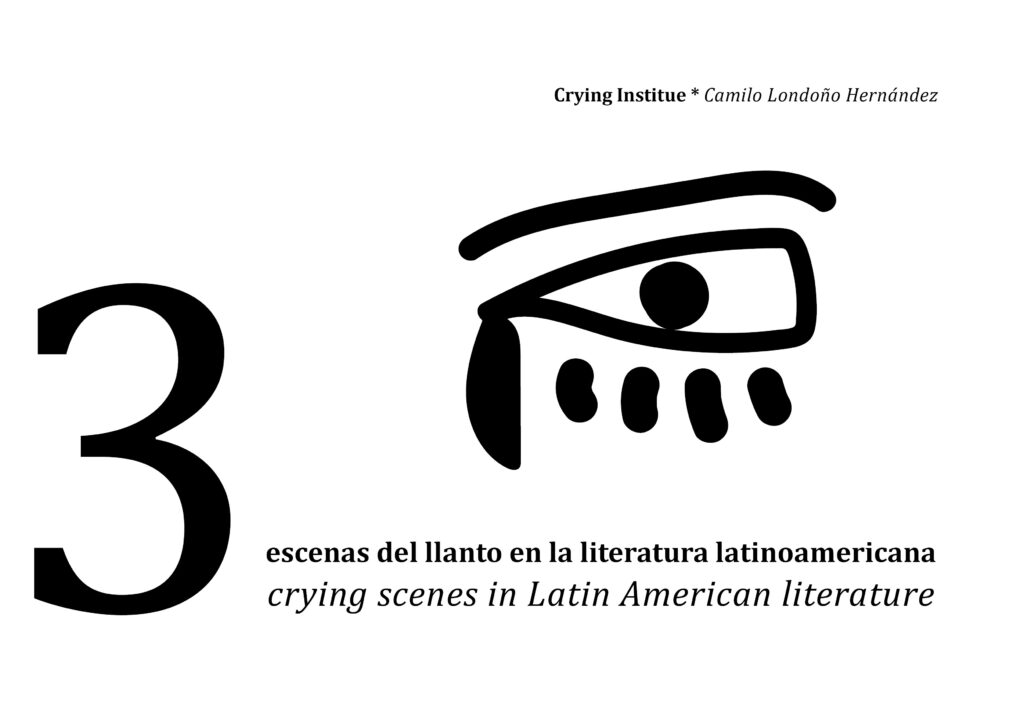

This is an open [personal] selection to share with my classmates at the Crying Institute. The procedure and methods to select them are based on personal affections and interpretations regarding crying and literature. Its curatorial process does not represent either a universal understanding of crying or a conclusive approach to Latin American literature.

[Spanish]

En la ceremonia, en un punto importante del despliegue, le pidieron hablar a las mujeres asistentes —mientras el tambor acompañaba a todas las que se autoreconocían como una —. Después, el turno de los hombres: sus voces retumbaban en el espacio con la seguridad de esa provocación. Me perdí, cuando se dirigió el agua a mí —encerrada en ese cuenco limitado por piel— la dejé pasar. Así me sintiera mujer, a pesar de haber sido condenada al nacer como hombre, no supe en qué momento hablar. No sentía la certeza ni la certidumbre de quienes tomaban el bastón, la palabra. Terminaron las dos rondas, por encima de mí, y guardé silencio, me aferré a la quietud de mis cuerdas vocales. No quería hablar en ningún momento, y el Peyote ya estaba dentro, en la fornicación orgánica entre la planta, la saliva y la sangre. Tenía que hablar, pero no bajo las condiciones que me torturaron durante la vida. El silencio fue mi grito más duro, la manifestación en contra de los binarismos que me persiguieron —incluso en las estrategias azarosas con las que pensé liberarme—. Me sentí extranjera, ajena, asustada.

El estruendo de mi incomodidad se escuchó a la luz del sol que tomamos, con la medicina. La abuela empezó a contar que ella y las que le anteceden no creían en lo masculino ni lo femenino como materialidades obvias, sino que, más bien, los pensaban como estados de una misma sustancia. El agua fue en ese momento la forma en la que ella compartía con nosotrxs su claridad para ver y entender los cuerpos —afirmando que eso la hacía sagrada—. Dijo que la masculinidad era como la lluvia, vertical, que iba a fertilizar la tierra para que el alimento brotara; que esa misma lluvia terminaba en el mar, en los ríos y en los cuerpos horizontales, en lo femenino, una gran placenta que se mueve dentro y paralela a la tierra. Mientras iba hablando, en un dúo de palabras con el abuelo que nos acompañaba, explicó cómo entendían las proyecciones, las imposiciones. Comprendí que el agua, al igual que el travestismo, era una de las invocaciones de la potencia salvaje del movimiento (por eso tantas religiones la incluyen en sus ceremonias). Cuando la abuela empezó a detallar su idea sobre el recinto donde nos encontrábamos, llovió —una invocación, garantía del tejido compartido—; llovió y comencé a llorar, fui lluvia vertical sobre mi cuerpa, como la limpia necesaria que iba apartándose en los labios y reconociéndose horizontal con la saliva. Me sentí aguacero ventiao´, del que cae en diagonal. Me reconocí salpicadura del río, directo al cielo cuando cuerpo impacta la superficie y se funde en ella. Me vi agua, nieve, tormenta en el mar. Lloraba, al ritmo del tambor con vientre líquido reconocía la herencia, un lugar en medio de las certezas binarias que contaminaban la comprensión de cualquier latitud. Sentí gozo, del que parecen sentir las personas que danzan en las iglesias de garaje. Alucinación o no, el tambor tocó a un ritmo con el que todxs empezaron a cantar mi nombre: Analú, A-na-lú, A-na-lú, A-na-lú. En esa etapa del camino que emprendía ya no era Ana; también había dejado de ser Luis, hace mucho. Ya era una diagonal.

Bajó la palabra a la cuerpa, a la piel preparada con saliva y llanto, llegué a casa y tomé la primera progynova y espironolactona con tres tragos de agua, la medicina “real”. Sumando los comprimidos farmacéuticos, aseguraba mi tránsito (el cóctel residual de occidente reflejado en pastilla y la ancestralidad del agua que empujaré en lo profundo de mí por lunas). Fui desecho, huérfana de espiritualidad indígena, pude gestar una nueva realidad. Me supe en las latitudes donde las estaciones no pesan, travesti.

***

[English]

In the ceremony, at an important point of the display, the women in attendance were asked to speak —while the drum accompanied all those who recognized themselves as one—. Then it was the turn of the men: their voices echoed in the space with the certainty of that provocation. I got lost. When the water was offered to me -enclosed in that bowl limited by the skin- I let it pass. Even though I felt like a woman, and despite having been condemned to be born as a man, I did not know at what moment to speak. I did not feel the certainty or the certainty of those who took the baton, the word. Over me, the two rounds ended. I kept silent, and clung to the stillness of my vocal curdles. I didn’t want to speak at any time, and the Peyote was already inside, in the organic fornication between plant, saliva, and blood. I had to speak, but not under the conditions that tortured me through life. The silence was my harshest cry, the manifestation of the binarism that haunted me —even in the haphazard strategies with which I thought to free myself—. I felt foreign, alien, and frightened.

The rumble of my discomfort was heard in the sunlight we took with the medicine. Grandmother began to tell how she and those before her did not believe in the masculine and feminine as obvious materiality but rather thought of them as states of the same substance. Water was, at that time, how she shared with us her clarity in seeing and understanding bodies-asserting that this made her sacred. She said that masculinity was like rain, vertical, that it was going to fertilize the earth so that food would sprout; that the same rain ended up in the sea, in the rivers, and the horizontal bodies, in the feminine, a great placenta that moves within and parallels to the earth. As she spoke, in a duet of words with the grandfather who accompanied us, she explained how they understood the projections, the impositions. I understood that water, like transvestism, was one of the invocations of the wild power of movement (which is why so many religions include it in their ceremonies). When the grandmother began to detail her idea about the enclosure where we were, it rained – an invocation, a guarantee of the shared fabric -; it rained, and I began to cry. I was vertical rain on my body like the necessary cleanliness moving away on the lips and recognizing itself horizontally with the saliva. I felt like a ventilated downpour, the kind that falls diagonally. I recognized myself as a splash of the river, straight to the sky when my body hits the surface and melts into it. I saw myself in water, snow, and storm in the sea. I cried to the rhythm of the drum with a liquid belly. I recognized the inheritance, a place in the middle of the binary certainties that contaminated the understanding of any latitude. I felt joy, the kind that people who dance in garage churches seem to feel. Hallucination or not, the drum beat to a rhythm with which everyone began to chant my name: Analú, A-na-lú, A-na-lú, A-na-lú, A-na-lú. At that stage of the road I was taking, I was no longer Ana; I had also stopped being Luis, a long time ago. I was already a diagonal.

The word got down to the body, to the skin prepared with saliva and tears. I came home and took the first progynova and spironolactone with three gulps of water, the “real” medicine. Adding the pharmaceutical tablets, I ensured my transit (the residual cocktail of the West reflected in the pill and the ancestrality of water that I will push deep inside me for moons). I was a waste, an orphan of indigenous spirituality, but I was able to gestate a new reality. I knew myself in the latitudes where the seasons do not weigh, transvestite.

***

2. Juan Rulfo. Es que somos muy pobres.

[It’s Because We’re So Poor]

https://agnionline.bu.edu/fiction/its-because-were-so-poor/

[Spanish]

La única esperanza que nos queda es que el becerro esté todavía vivo. Ojalá no se le haya ocurrido pasar el río detrás de su madre. Porque si así fue, mi hermana Tacha está tantito así de retirado de hacerse piruja. Y mamá no quiere.

Mi mamá no sabe por qué Dios la ha castigado tanto al darle unas hijas de ese modo, cuando en su familia, desde su abuela para acá, nunca ha habido gente mala. Todos fueron criados en el temor de Dios y eran muy obedientes y no le cometían irreverencias a nadie. Todos fueron por el estilo. Quién sabe de dónde les vendría a ese par de hijas suyas aquel mal ejemplo. Ella no se acuerda. Le da vueltas a todos sus recuerdos y no ve claro dónde estuvo su mal o el pecado de nacerle una hija tras otra con la misma mala costumbre. No se acuerda. Y cada vez que piensa en ellas, llora y dice: “Que Dios las ampare a las dos.” Pero mi papá alega que aquello ya no tiene remedio. La peligrosa es la que queda aquí, la Tacha, que va como palo de ocote crece y crece y que ya tiene unos comienzos de senos que prometen ser como los de sus hermanas: puntiagudos y altos y medio alborotados para llamar la atención. -Sí -dice-, le llenará los ojos a cualquiera dondequiera que la vean. Y acabará mal; como que estoy viendo que acabará mal. Ésa es la mortificación de mi papá.

Y Tacha llora al sentir que su vaca no volverá porque se la ha matado el río. Está aquí a mi lado, con su vestido color de rosa, mirando el río desde la barranca y sin dejar de llorar. Por su cara corren chorretes de agua sucia como si el río se hubiera metido dentro de ella. Yo la abrazo tratando de consolarla, pero ella no entiende. Llora con más ganas. De su boca sale un ruido semejante al que se arrastra por las orillas del río, que la hace temblar y sacudirse todita, y, mientras, la creciente sigue subiendo. El sabor a podrido que viene de allá salpica la cara mojada de Tacha y los dos pechitos de ella se mueven de arriba abajo, sin parar, como si de repente comenzaran a hincharse para empezar a trabajar por su perdición.

***

[English]

Our only hope is that the calf is still alive. Perhaps he didn’t think of crossing the river behind his mother. Because if he did, my sister Tacha is just this far away from becoming a whore. And mother doesn’t want that.

My mother doesn’t know why God has punished her by giving her such daughters, since in her family, from my grandmother on, there have never been bad people. Everybody was raised with the fear of God, and very obedient, and didn’t offend anyone. Everyone was that way. Who knows where her two daughters learned such bad behavior? She can’t figure it out. She wracks her brain and it isn’t clear where she went wrong or what sin she committed to have given birth to one bad daughter after another. She can’t figure it out. And every time she thinks of them, she weeps and says: “God help them.”

My father says there’s nothing to be done at this point. The one at risk is the daughter who is still here, Tacha, who keeps on growing and growing and whose breasts are already beginning to show, and which promise to be like her sisters’: pointy and high and pert and attention-getting. “Yes,” he says, “they’ll stare at her wherever she goes. It will all end badly; I can already see it will all end badly.” That’s why my father is terrified.

Tacha cries when she thinks her cow won’t come back because the river has killed it. She’s right here at my side, in her pink dress, looking at the river from the top of the ravine, unable to stop crying. Streams of dirty water run down her face, as if the river were inside her.

I put my arms around her, trying to comfort her, but she doesn’t understand. She cries even more. A sound similar to the one sweeping along the riverbanks emerges from her lips, making her shiver, and she trembles all over. The crest rises. the rotten smell from below speckles Tacha’s wet face. Her two little breasts bob up and down, continually, as if they had suddenly begun to swell, bringing her ever closer to perdition.

***

3. Oliverio Girondo. Llorar a lágrima viva. [Weep living tears!]

[Spanish]

Llorar a lágrima viva.

Llorar a chorros.

Llorar la digestión.

Llorar el sueño.

Llorar ante las puertas y los puertos.

Llorar de amabilidad y de amarillo.

Abrir las canillas,

las compuertas del llanto.

Empaparnos el alma, la camiseta.

Inundar las veredas y los paseos,

y salvarnos, a nado, de nuestro llanto.

Asistir a los cursos de antropología, llorando.

Festejar los cumpleaños familiares, llorando.

Atravesar el África, llorando.

Llorar como un cacuy, como un cocodrilo…

si es verdad que los cacuíes y los cocodrilos

no dejan nunca de llorar.

Llorarlo todo, pero llorarlo bien.

Llorarlo con la nariz, con las rodillas.

Llorarlo por el ombligo, por la boca.

Llorar de amor, de hastío, de alegría.

Llorar de frac, de flato, de flacura.

Llorar improvisando, de memoria.

¡Llorar todo el insomnio y todo el día!

***

[English]

Weep living tears!

Weep gushers!

Weep your guts out!

Weep dreams!

Weep before portals and at ports of entry!

Weep in fellowship! Weep in yellow!

Open the locks and calas of tears!

Let us soak our shirts, our souls!

Inundate the sidewalks and the boulevards,

and bear us along safely on the flood!

Assist in anthropology courses, weeping!

Celebrate relative’s birthdays, weeping!

Walk across Africa, weeping!

Weep like a caiman, like a crocodile…

especially if it’s true that caimans and crocodiles

have no real tears in them.

Weep anything, but weep well!

Weep with your nose, with your knees!

Weep through your navel, through your mouth!

Weep of love, of hate, of happiness!

Weep in your frock, from flatus, from frailty!

Weep impromptu, weep from memory!

Weep throughout the insomniac night

and throughout the livelong day!

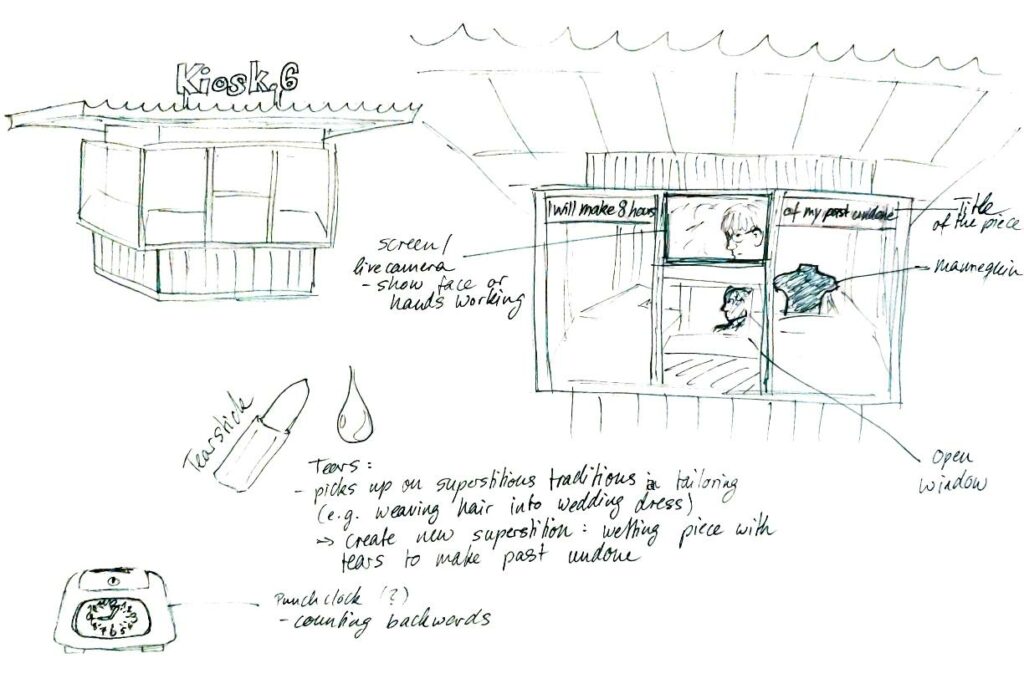

The aim of this project is to create a performance that will last for eight hours – the normalized span of a working day (at least in Western-European conceptions of employment). The performance refers to my personal past, working as a tailor for several studios and workshops.

I will invest eight hours of labor in undoing my own work by taking apart a jacket that I have made myself (within more than 60 hours of handcrafting).

The performance should take place in a shop window.

The performance will take place during summaery 2023.

The project poses questions of what it takes to undo or erase – what can possibly be undone through the process of taking apart and what new things, objects, ideas, feelings, memories, and values emerge from it?

Is it possible to undo work? And with it erase passed time? Ultimately, will it be possible to undo time?

+ The performance will happen inside Kiosk.6 at Sophienstiftplatz, Weimar.

The performance will take 8 hours. Within the 8 hours I will take apart a jacket that I have made myself during my apprenticeship stitch by stitch.

+ With me in the Kiosk there will be the jacket, a chair, the tools I need to take it apart, an empty mannequin, a punchclock and a camera. The singled out pieces of the jacket will fill up the window displays bit by bit.

The camera will be directed at my face, covered in tears, or at my hands by turns.

+ The front window of the kiosk will be open to enable interaction with passers-by.

Above the window there will be a screen showing what the live-camera captures.

Next to the screen the title of the performance is displayed.

+ Every hour (starting on hour 0) I will punch the punchclock, that is programmed to count backwards. I will also use a tear-stick to make my lacrimal sacs produce tears.

+ The performance ends when the 8 hours have passed. By the end all pieces of the jacket shall be detached from each other.

In tailoring, like in many artisan traditions, there are a lot of superstitions intertwined with the craft. They mostly connect with abjects of the body of the artisan, produced while working on a piece. For example: In Germany, when making a wedding dress, a drop of blood should be placed somewhere at the inlay – which is supposed to bring good luck and help for a happy marriage (it also used to symbolize bloodline and a mother’s grieve, as the mother of a bride was supposed to sew her wedding dress). In France, unmarried embroiderers would sew in one of their own hair into a wedding dress, in order to be the next one to marry.

I decided to create a new superstitious tradition, making use of my tears. By crying while opening the seams of my jacket, I can make the past undone.

At the same time, the meanings of the tears – like those of the drop of blood – are manifold. They symbolize superstition, but they could also flow because of grieve, trauma, fear, melancholy, or relieve. They catalyze negative emotions and wash them out.