A performance by Paula Kiermaier in Athens (Athens School of Fine Arts), June 2023

Material I used:

plastic bag, my collection of stones and little metal objects, water and a nail

Sketch to explain, how the procedure was:

A performance by Paula Kiermaier in Athens (Athens School of Fine Arts), June 2023

Material I used:

plastic bag, my collection of stones and little metal objects, water and a nail

Sketch to explain, how the procedure was:

We wish Ana Mendieta was still alive. A performative intervention to remember the Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta.

“No one knows what truly happened on that late-summer morning in 1985. What remains unacceptable, however, is yet another example of a woman’s career being defined by the relative success of her husband, of a female artist’s legacy overshadowed by her tragic biography while her husband’swork remains relatively untouched by it” (1)

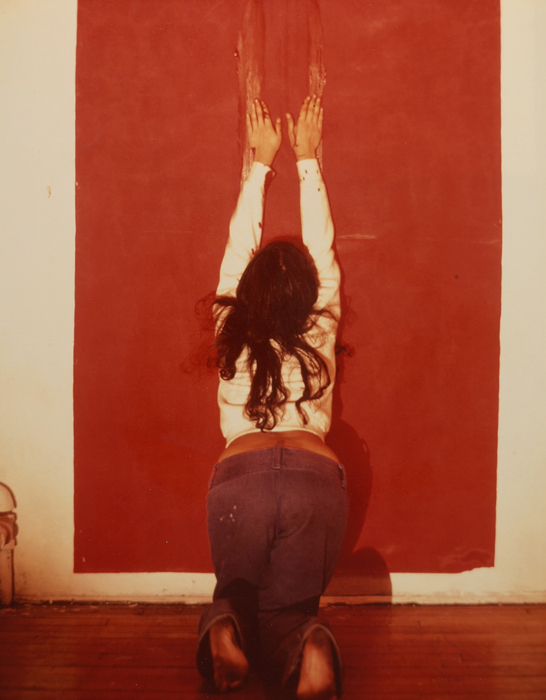

Ana Mendieta, Body Tracks, 1974 (2)

(In 1985 Ana fell to her death from her apartment in Greenwich Village, causing a stir in the art world. She had a tumultuous marriage to artist Carl Andre, who many believed was involved in her death. Despite lacking eyewitnesses, Andre was acquitted in 1988 after a three-year trial. The support that Andre received from individuals in the art world, who appeared to be more concerned with advancing his career and shielding him, was deeply surprising to many. Their apparent indifference to whether he had committed the murder left many in shock.)

Short note about Ana Mendieta (1948–1985)

. born in Cuba

. Mendieta moved to Iowa at the age of 12 along with her sister through a US government asylum initiative for young people following the Cuban revolution

. initially trained as a painter, changed to the university’s newly established MFA in Intermedia program, where she began shaping her interdisciplinary art

. during her graduate studies, Mendieta initiated her first performances and photografic records (around the theme of violence against women, suffering experienced by the female body)

.throughout her career, Mendieta’s explorations of representation were firmly rooted in an intersectional understanding of identity, where considerations of race, gender, age, and class coexisted. (7)

Ana Mendieta, Silueta series in Mexico, 1976 (3)

Intervention

Because Ana was not mentioned at her husbands large retrospective exhibition in New York, the collective called No Wave Performance Task Force (“[…] a flexible collective in New York that enables performative social sculpture, practicing Feminist construction rather than reacting solely to existing conditions of patriarchy, gender, sexuality […]”4) carried out a series of interventions at the exhibition venues Dia Foundation in Beacon and Chelsea.

These interventions aimed to rekindle a discussion about Mendieta by opposing her work with Andre’s elegant geometric sculptures.

One of those interventions, mentioned before, was the following event in 2015: “CRYING; A PROTEST”

No Wave Performance Task Force, CRYING; A PROTEST, 2015 (5)

In this event fifteen feminist artists, poets, and activists gathered in the museum’s galleries to mourn Ana Mendieta’s memory. Their intense emotional reactions, in stark contrast to Andre’s “refined” geometric art, likely seemed especially disruptive to other visitors and gallery staff.

“Crying is often seen as a sign of weakness, of emotional excess, and coded as feminine. As a group, though, our tears were seen as a disruption — a threat. Like much of Ana Mendieta’s art, our performance was ephemeral.” (2)

The feminist group effectively transformed the indifferent aestheticism of Andre’s minimalism into an emotionally charged site of mourning instead of only grief. His geometric structures were repurposed as memorials to Mendieta.

Emotionality plays a significant role in Ana’s works too. To remember her and keep her art alive, I want to show some more photos of her works:

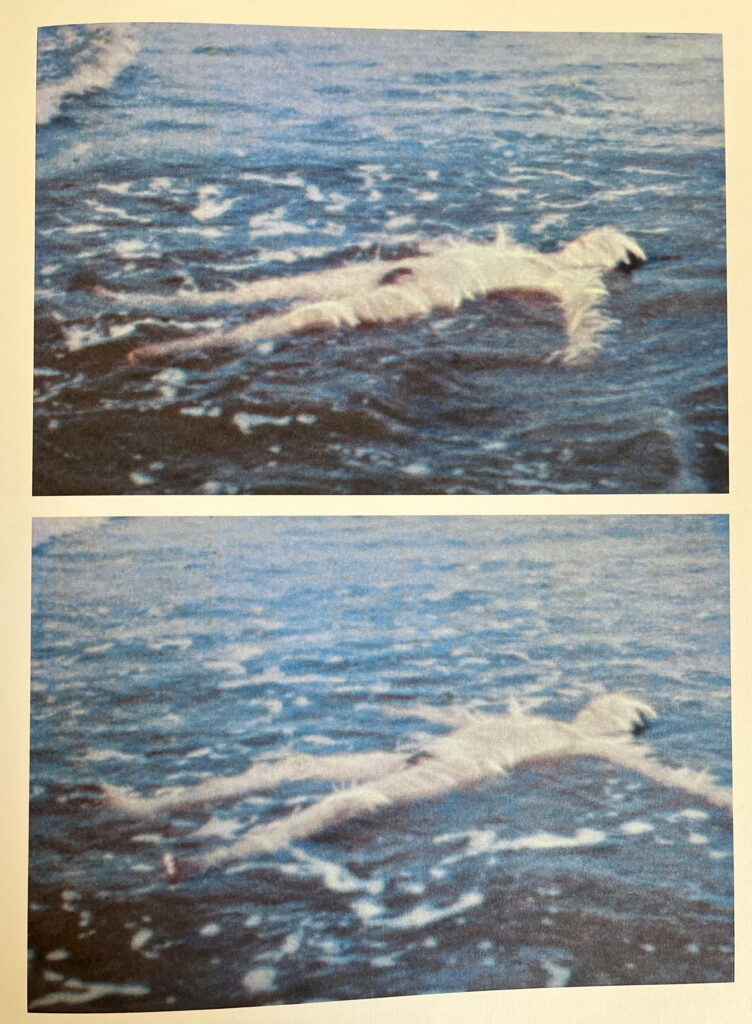

Ana Mendieta, Ocean Bird Wash Up, 1974 (6)

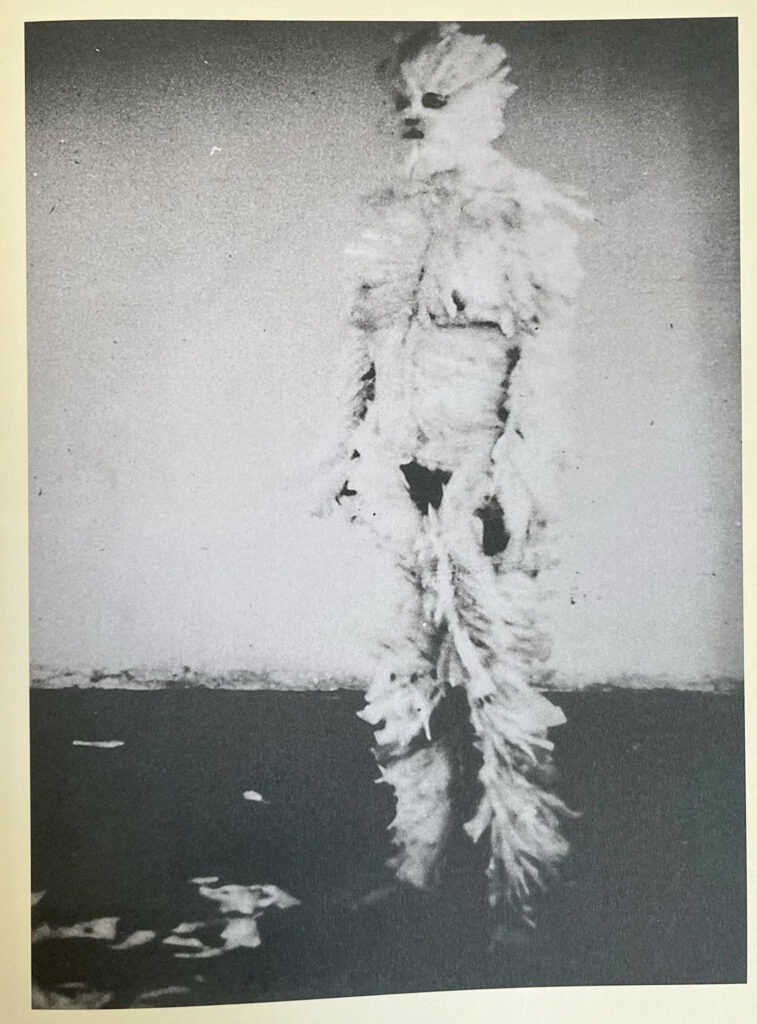

Ana Mendieta, Bird Transformation, 1972 (6)

Ana Mendieta, Blood and Feathers, 1974 (6)

Ana Mendieta, untitled (Guanobo), 1981 (6)

References:

(1) A. Castro (2015). The Weeping Wall: The Mendieta Case. esse arts + opinions, 85 , pp. 76–78. https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/esse/2015-n85-esse02064/78603ac.pdf [accessed 18.10.2023]

(2) Ana Mendieta (1974). Body Tracks. [colour photograph, 25 × 20 cm] https://artreview.com/ar-april-2018-feature-ana-mendieta/ [accessed 18.10.2023]

(3) Ana Mendieta (1976). Untitled from Silueta series in Mexico. [C-print on Kodak Professional paper] https://scma.smith.edu/blog/performed-invisibility-ana-mendietas-siluetas [accessed 18.10.2023]

(4) https://www.facebook.com/nowavetaskforce/ [accessed 18.10.2023]

(5) M. Crawford (2015). Crying for Ana Mendieta at the Carl Andre Retrospective. https://hyperallergic.com/189315/crying-for-ana-mendieta-at-the-carl-andre-retrospective/ [accessed 18.10.2023]

(6) S. Rosenthal (2014). Ana Mendieta – Traces. Hatje Cantz Verlag.

(7) A. Pucker. Z. Lukov. Ana Mendieta. Art In Common. https://www.artincommon.art/ana-mendieta-bbt [accessed 21.10.2023]

Am Dienstag, 4.7.2023, wird zwischen 10 und 18 Uhr die Performance

I WILL MAKE 8 HOURS OF MY PAST UNDONE.

von Marin Müller im Kiosk.6 (Sophienstiftsplatz, Weimar) stattfinden.

Weiteres: https://cryinginstitute.artnextsociety.net/2023/03/29/i-will-make-eight-hours-of-my-past-undone/

Next Tuesday, 4.7.2023, between 10 am and 6 pm, the performance

I WILL MAKE 8 HOURS OF MY PAST UNDONE.

by Marin Müller will take place at Kiosk.6 (Sophienstiftsplatz, Weimar) .

Further: https://cryinginstitute.artnextsociety.net/2023/03/29/i-will-make-eight-hours-of-my-past-undone/

Das Sad Clown Paradox beschreibt ist Phänomen, welches Menschen, die als Comedians oder Entertainer auf der Bühne stehen und andere zum Lachen bringen, jedoch selbst meist an psychischen Erkrankungen leiden oder oft mit negativen Gefühlen zu kämpfen haben beschreibt. Nach einer Studie von 1975 vom Psychotherapeuten Samuel Janus in der er und seine Kolleg*innen 69 erfolgreiche und berühmte Comedians befragt hat, haben die meisten Befragten einen überdurchschnittlichen IQ, erleben jedoch auch häufige negative Emotionen, Anxiety oder Depressionen. Humor kann in schwierigen Lebenslagen helfen, für Zuschauer*innen und den Comedian. Selbstmissbiligender Humor hingegen kann ein Risikofaktor für die mentale Gesundheit sein.

Sad Clowns sind ein Phänomen der Popkultur, damit ist nicht das oben beschriebene Paradox gemeint, sondern buchstäblich die traurige Clownsfiguren, Krusty the Clown von den Simpson oder der Joker usw.

Bei meiner Recherche bin ich auf Puddles aufmerksam geworden. Puddles ist ein trauriger Clown, der nicht vorgibt glücklich zu sein, er will sein Publikum nicht zum Lachen bringen. Er zelebriert das traurig sein, das Weinen und all die negativen Emotionen die damit einhergehen. Seine Show heißt »Puddles Pity Party«, in dieser performt er auf der Bühne indem er Cover von berühmten Lieder singt, ohne dabei zwischendurch zu sprechen. Er transportiert alles, was er sagen möchte, durch seine Geste und Mimik. Puddles hat eine große Fangemeinde, beim Durchscrollen der Kommentare unter seinen Youtube Videos sind mir zahlreiche Kommentare aufgefallen, in den Menschen beschreiben, dass sie seit Jahren nicht weinen können und nun durch Puddles bestimmte Emotionen getriggert wurden, die sie weinen ließen.

Ich frage mich, warum diese Menschen bei einem traurigen Clown, der ein Cover von Halleluja singt, seit Jahren das erste Mal wieder richtig weinen können, selbst bei einschneidenden traumatischen Erlebnissen die Tränen zurückgeblieben sind, aber jetzt alles aus ihnen herausbricht. Viele beschreiben, dass Puddles für sie einen Raum erschafft, in dem es okay ist, traurig zu sein, in dem man sich nicht für seine Tränen schämen muss. Er habe etwas sehr pures und ehrliches und verbindet sich so mit dem Publikum in einer Weise, wie viele sich nicht mit ihren eigenen negativen Gefühlen verbinden können.

By Xiuyi Wu and Yumiko Mita

Crying Culture in CHINA

In China, crying in front of others has generally been seen as shameful. East Asian society as a whole, including Chinese culture, prefers implicitly expressed emotions. However, many people in China view crying as a privilege for women because there are some circumstances in which it is understandable. This phenomena may then be thoroughly examined, and we will discover

that this exemption does not represent preferential treatment for women.

哭嫁 (Crying Marriage):

Crying marriage is an ancient Chinese wedding custom, now common in some remote areas of rural southern China, in which the bride performs a ritual crying at the time of her wedding. Depending on regional customs, crying usually begins about a month before the wedding, when the bride begins to cry and friends and relatives will weep along with her. It is said that the bride is considered unlucky and even condemned by the public if she does not cry.

Lyrics in Crying: The Sadness of Separation

In some rural communities, a married daughter is compared to spilled water, and it is shameful for her to go back to her mother’s family after her marriage. Therefore, once these ladies get married, it is quite difficult for them to see their parents, relatives, and childhood friends.

Complaint against Marriage

In the past, women did not have enough liberty to choose their spouses, and a lot of marriages were arranged by the parents of the bride and groom. It was incredibly frightening to get married to someone you had never met, so it was crucial to express displeasure with this convention and complaints against society in the lyrics of Cry.

Overview

East Asian social anthropologist Choi Kilsong writes in his book, Cultural Anthropology of Crying (哭きの文化人類学), that Hakka (,客家, Chinese ethnic group) women are largely uneducated and that Hakka society is utterly patriarchal and male-centered. It is stated that women only cry to show their emotions on the seldom occasions of weddings and funerals, and that this was the only occasion where they had the freedom to express their emotions. At village gatherings, women are not allowed to speak. Even when elder women speak up, their opinions are rarely taken seriously.

Freedom to cry

Although most developed regions of China have abandoned this tradition, women have always faced varied degrees of inequality in both life and the workplace due to patriarchal society. Whether being forced to cry, or having the privilege of crying because it is seen as vulnerable are something Chinese women want to have.

Crying Culture in JAPAN

Data from the International Study on Adult Crying suggest that, of the 37 nationalities polled, the Japanese are among the least likely to cry. (Americans, by contrast, are among the most likely.)

“Hiding one’s anger and sadness is considered a virtue in Japanese culture,” a Japanese psychiatrist told the newspaper Chunichi Shimbun in 2013.

涙活 (Rui-Katsu):

It’s safe to say we all have much to cry about these days. People are encouraging one another to express mental distress: Even leaders are crying in public. And that’s OK: Crying can be really, really good for you. And that’s the message that Hidefumi Yoshida, a self-described tears teacher, is out to share. He holds workshops across Japan, where he helps grown-ups learn to cry. Whether it’s breaking the stigma around crying out of grief or simply learning to weep for better mental health, it’s a lesson we all could probably embrace a little more right now.

E.g. The Man Teaching Japan to Cry

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ih1l-FR508o&ab_channel=BBCReel

Culturally Appropriate Crying: Gatherings

When one person starts crying, it is a cue for others to cry. This may be due to peer pressure, or to practice homogeneity. People are usually expected to cry when there is a celebration (e.g. Birthday) with alcohol, or when there is a touching moment (e.g. baseball event).

“Cry-Baby”

Women are expected to cry more than men. The gender stereotype that Japanese women are “cry-babies” and emotional are ingrained. Thus, men expect women to cry at any inconvenience that may arise. This is translated to the anime culture as well.

Overview

● Japanese people are most unlikely to express mental distress

● “Hiding one’s anger and sadness is considered a virtue in Japanese culture”

● Tear teacher, Hidefumi Yoshida, started a movement called “Rui-katsu” (Tear Activity) that encourages people to cry

● While expressing distress or strong emotions are uncommon, Japanese people tend to express their true emotions at gatherings that involve alcohol.

● There are also cultural expectations that when one starts to cry, others join in. Women are expected to cry more than men.

CONCLUSION

● While there are differences, China and Japan are both repressive when it comes to expressing emotions. Therefore, many people suffer from mental health issues.

● Crying could be the best practice to regain health, balance in life, especially when our lifestyles have vastly changed and become limited during COVID-19.

● Letting out emotions should not be a taboo; rather encouraged. People should be free to express themselves regardless of societal pressure.

Public performance, Chemnitz, Jan, 2022

Rand Ibrahim

Photography: Leila Keivan

Could a person carry all the grief in the world?

Is that an exaggeration? An overrated dramatic scene?

One day you read in the news: a gang of rats ate an infant’s face

Then you look to the corner of the street and you see a child kicking a dog until he breaks every little rip in his chest.

“Women are still raped and dumped in trash containers”.

On another day, you can extract colorful fragments out of the belly of a smelly dead fish with rotten eyes, which was in the market for people to buy and eat.

There are many reasons to make you cry and burden you with grief and sorrow, not to mention the personal ones.

Sensitivity is a problem

Where did I learn that from?…

When did I learn that?

Photography: Leila Keivan

You were born sensitive; spend your first years crying over anything that does not suit your moody existence.

Your sensitivity contracts while you observe the behaviour of the maniac adults around you.

Your little size friends in school, those who were trained better

will make you realise you should preserve and keep your tears to yourself, just in case you want to survive the next day.

This time a kid will hit me and I will not cry,

I will hit back.

This time they will bomb us,

I will not cry.

I will survive.

It keeps going on until you understand, your tears are valuable, you should only shed them when it is necessary. I will save my tears for the worthy but I am thirty-years old now, and my tears cannot stop running metaphorically.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1pxxmYGqEmFICI2XI5GPL8GKErZY9168m/view?usp=sharing

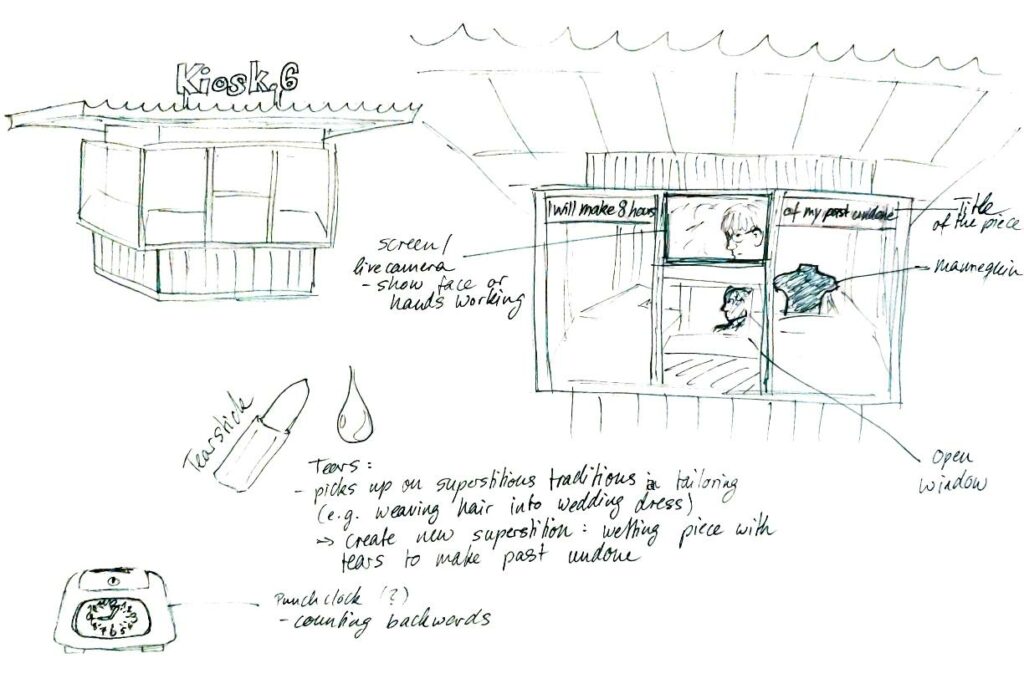

The aim of this project is to create a performance that will last for eight hours – the normalized span of a working day (at least in Western-European conceptions of employment). The performance refers to my personal past, working as a tailor for several studios and workshops.

I will invest eight hours of labor in undoing my own work by taking apart a jacket that I have made myself (within more than 60 hours of handcrafting).

The performance should take place in a shop window.

The performance will take place during summaery 2023.

The project poses questions of what it takes to undo or erase – what can possibly be undone through the process of taking apart and what new things, objects, ideas, feelings, memories, and values emerge from it?

Is it possible to undo work? And with it erase passed time? Ultimately, will it be possible to undo time?

+ The performance will happen inside Kiosk.6 at Sophienstiftplatz, Weimar.

The performance will take 8 hours. Within the 8 hours I will take apart a jacket that I have made myself during my apprenticeship stitch by stitch.

+ With me in the Kiosk there will be the jacket, a chair, the tools I need to take it apart, an empty mannequin, a punchclock and a camera. The singled out pieces of the jacket will fill up the window displays bit by bit.

The camera will be directed at my face, covered in tears, or at my hands by turns.

+ The front window of the kiosk will be open to enable interaction with passers-by.

Above the window there will be a screen showing what the live-camera captures.

Next to the screen the title of the performance is displayed.

+ Every hour (starting on hour 0) I will punch the punchclock, that is programmed to count backwards. I will also use a tear-stick to make my lacrimal sacs produce tears.

+ The performance ends when the 8 hours have passed. By the end all pieces of the jacket shall be detached from each other.

In tailoring, like in many artisan traditions, there are a lot of superstitions intertwined with the craft. They mostly connect with abjects of the body of the artisan, produced while working on a piece. For example: In Germany, when making a wedding dress, a drop of blood should be placed somewhere at the inlay – which is supposed to bring good luck and help for a happy marriage (it also used to symbolize bloodline and a mother’s grieve, as the mother of a bride was supposed to sew her wedding dress). In France, unmarried embroiderers would sew in one of their own hair into a wedding dress, in order to be the next one to marry.

I decided to create a new superstitious tradition, making use of my tears. By crying while opening the seams of my jacket, I can make the past undone.

At the same time, the meanings of the tears – like those of the drop of blood – are manifold. They symbolize superstition, but they could also flow because of grieve, trauma, fear, melancholy, or relieve. They catalyze negative emotions and wash them out.

I cry to purge.

To cleanse my body.

And let go of the pressure.

Catharsis (Ancient Greek: κάθαρσις) is a term often used to describe that state of purification. Most prominently described in Artistotle’s Poetics, it was in ancient times and is still today in use as a means of narration. Aristotle found catharsis mainly in the dramatic form of tragedy. The staging of a tragedy evokes a state in the audience that ought to purge them of negative sentiments. This is achieved through mimesis (imitation or simulation) of actions. Poetic text and theatrical acting together induce a more or less intense simulation, depending on the skill of their originators – according to Aristotle. A good mimesis then provokes those two things called éleos and phóbos in the spectator.

Pity and Fear are commonly used as the English translation of éleos and phóbos. Within German speaking studies though, their corresponding terms „Mitleid“ und „Furcht“ (a translation originating from G. E. Lessing) would be criticised as imprecise. Therefore a more accurate description of what induces catharsis would be lament/ emotion (Jammer/ Rührung) on one side and terror/ shudder (Schrecken/ Schauder) on the other.

A good catharsis is meant to help me cleanse my passions or sentiments. As I watch the protagonist go through intense states on stage (or respectively: on screen, in a novel, in a telenovela etc.) I feel for them. I take a stance towards the mimetic simulation in which my sentient and, what’s more, my moral compass are shaped. Catharsis, throughout history, was therefore frequented as an instrument for moral and politcal education – bearing in itself, of course, the immediate potential of misuse.

In a psychological sense, the element of catharsis is also in use, very pracitcally, to cleanse from traumatic experiences or to handle negative memories. There are various methods in psychoanalysis and psychotherapy that attempt to induce cathartic moments, hoping to heal wounds. (see, for example: anger therapy (S. Freud), psychodrama (J.L. Moreno))

The importance of telling stories of trauma, and with it building a bridge between the literary and the psychological sense of catharsis, is pointed out by philosopher Richard Kearny:

„Cathartic healing involves the narrating of past wounds both as they happened and as if they happened in this way or that. And it is precisely this double response of truth (as) and fiction (as-if) that emancipates us from our habitual protection and denial mechanisms. One suddenly experiences oneself as another and the other as oneself – and thereby begin to apprehend otherwise unapprehendable pain.“

Kearny, Richard: „Narrative Imagination and Catharsis.“ Academia.edu, n.d., https://www.academia.edu/34439052/Narrative_Imagination_and_Catharsis. Accessed 10 Jan. 2023.

References:

Abd Elsalam, Dina: „Psychodrama and Sociodrama: Aristotelian Catharsis Revisited.“ Alexandria, UP, 2015.

Aristoteles: „Poetik.“ Translation by Manfred Fuhrmann. Stuttgart, Philipp Reclam, 1982.

Cherry, Kendra: „What is Catharsis?“ Verywell mind, 20 Aug. 2022, https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-catharsis-2794968. Accessed 10 Jan. 2023.

Halliwell, Stephen: „Katharsis.“ Encyclopedia.com, 2005, https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/katharsis. Accessed 10 Jan. 2023.

Katharsis. Dorsch: Lexikon der Psychologie, n.d., https://dorsch.hogrefe.com/stichwort/katharsis. Accessed 12 Jan. 2023.

Kearny, Richard: „Narrative Imagination and Catharsis.“ Academia.edu, n.d., https://www.academia.edu/34439052/Narrative_Imagination_and_Catharsis. Accessed 10 Jan. 2023.

Sabata, Valeria: „Die Bedeutung der Katharsis in der Psychologie.“ Gedankenwelt, 15 Nov. 2021, https://gedankenwelt.de/die-bedeutung-der-katharsis-in-der-psychologie/. Accessed 10 Jan. 2023.

The Meaning of Catharsis in Freudian Theory. Act For Libraries, n.d., http://www.actforlibraries.org/the-meaning-of-catharsis-in-freudian-theory/. Accessed 10 Jan. 2023.