A performance by Paula Kiermaier in Athens (Athens School of Fine Arts), June 2023

Material I used:

plastic bag, my collection of stones and little metal objects, water and a nail

Sketch to explain, how the procedure was:

A performance by Paula Kiermaier in Athens (Athens School of Fine Arts), June 2023

Material I used:

plastic bag, my collection of stones and little metal objects, water and a nail

Sketch to explain, how the procedure was:

A book I once held sobbed, its tears falling over my fingertips.

A tremendous sorrow that it was unable to bear left its pages soggy, resembling a ship of sailors.

The ink on the page began to stream like rain as the words inside had come to life.

It had thrived because of the stories that were told, but now it cried out in pain.

I questioned why the book was crying.

The pages then shifted to stories of loss and sad farewells.

Hearts still burned for unrequited love.

The book had lived a thousand lives and experienced every one of them with agony. It cried for everyone it had survived and for those it was unable to comfort.

Because even books must experience their fair share of grief in the lonely night, I wiped away its tears as I held it gently still and squeezed it tightly.

Then I lowered my voice and said to the book, “Hope, love, and all that is brilliant.” I added that even though the book was dripping with tears, the pages still gleamed in the light.

Books may cry, as can we all, but through their sorrow, we discover the truth: that although life is difficult, it is true that joy can arise from the depths of childhood.

Das Sad Clown Paradox beschreibt ist Phänomen, welches Menschen, die als Comedians oder Entertainer auf der Bühne stehen und andere zum Lachen bringen, jedoch selbst meist an psychischen Erkrankungen leiden oder oft mit negativen Gefühlen zu kämpfen haben beschreibt. Nach einer Studie von 1975 vom Psychotherapeuten Samuel Janus in der er und seine Kolleg*innen 69 erfolgreiche und berühmte Comedians befragt hat, haben die meisten Befragten einen überdurchschnittlichen IQ, erleben jedoch auch häufige negative Emotionen, Anxiety oder Depressionen. Humor kann in schwierigen Lebenslagen helfen, für Zuschauer*innen und den Comedian. Selbstmissbiligender Humor hingegen kann ein Risikofaktor für die mentale Gesundheit sein.

Sad Clowns sind ein Phänomen der Popkultur, damit ist nicht das oben beschriebene Paradox gemeint, sondern buchstäblich die traurige Clownsfiguren, Krusty the Clown von den Simpson oder der Joker usw.

Bei meiner Recherche bin ich auf Puddles aufmerksam geworden. Puddles ist ein trauriger Clown, der nicht vorgibt glücklich zu sein, er will sein Publikum nicht zum Lachen bringen. Er zelebriert das traurig sein, das Weinen und all die negativen Emotionen die damit einhergehen. Seine Show heißt »Puddles Pity Party«, in dieser performt er auf der Bühne indem er Cover von berühmten Lieder singt, ohne dabei zwischendurch zu sprechen. Er transportiert alles, was er sagen möchte, durch seine Geste und Mimik. Puddles hat eine große Fangemeinde, beim Durchscrollen der Kommentare unter seinen Youtube Videos sind mir zahlreiche Kommentare aufgefallen, in den Menschen beschreiben, dass sie seit Jahren nicht weinen können und nun durch Puddles bestimmte Emotionen getriggert wurden, die sie weinen ließen.

Ich frage mich, warum diese Menschen bei einem traurigen Clown, der ein Cover von Halleluja singt, seit Jahren das erste Mal wieder richtig weinen können, selbst bei einschneidenden traumatischen Erlebnissen die Tränen zurückgeblieben sind, aber jetzt alles aus ihnen herausbricht. Viele beschreiben, dass Puddles für sie einen Raum erschafft, in dem es okay ist, traurig zu sein, in dem man sich nicht für seine Tränen schämen muss. Er habe etwas sehr pures und ehrliches und verbindet sich so mit dem Publikum in einer Weise, wie viele sich nicht mit ihren eigenen negativen Gefühlen verbinden können.

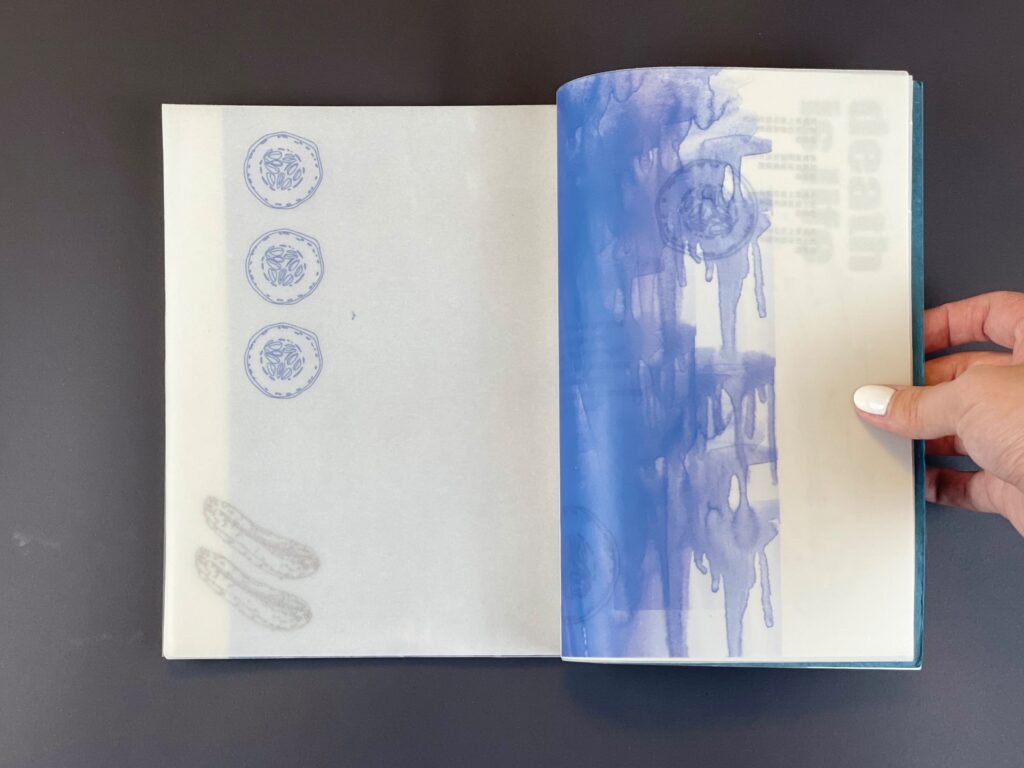

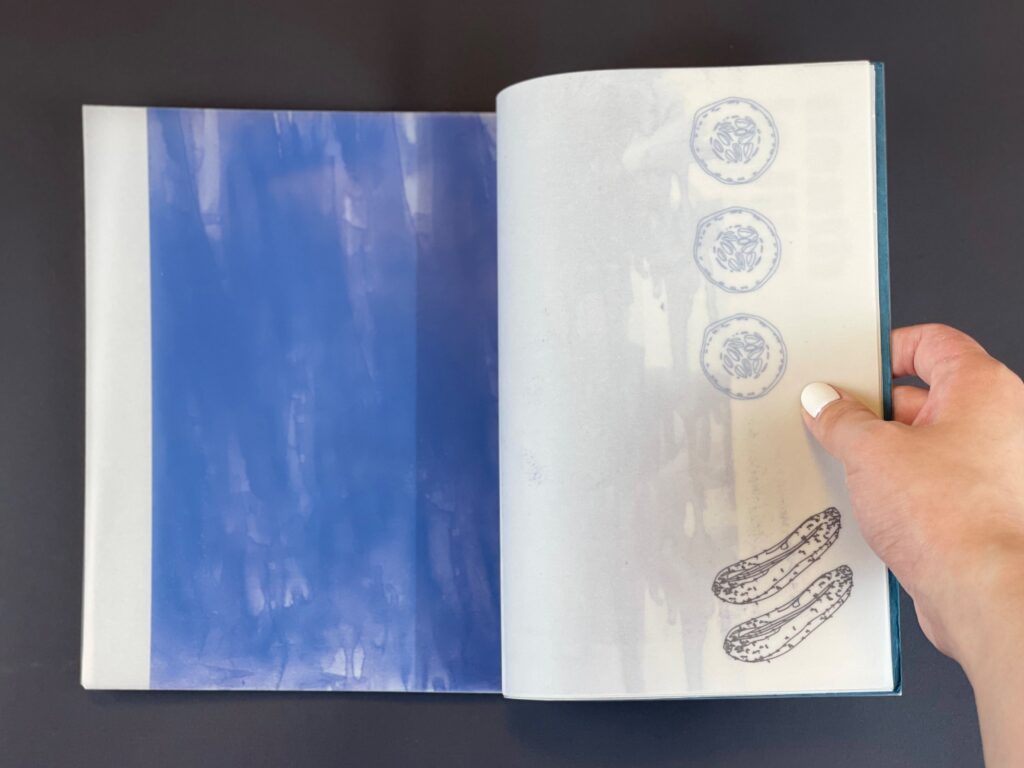

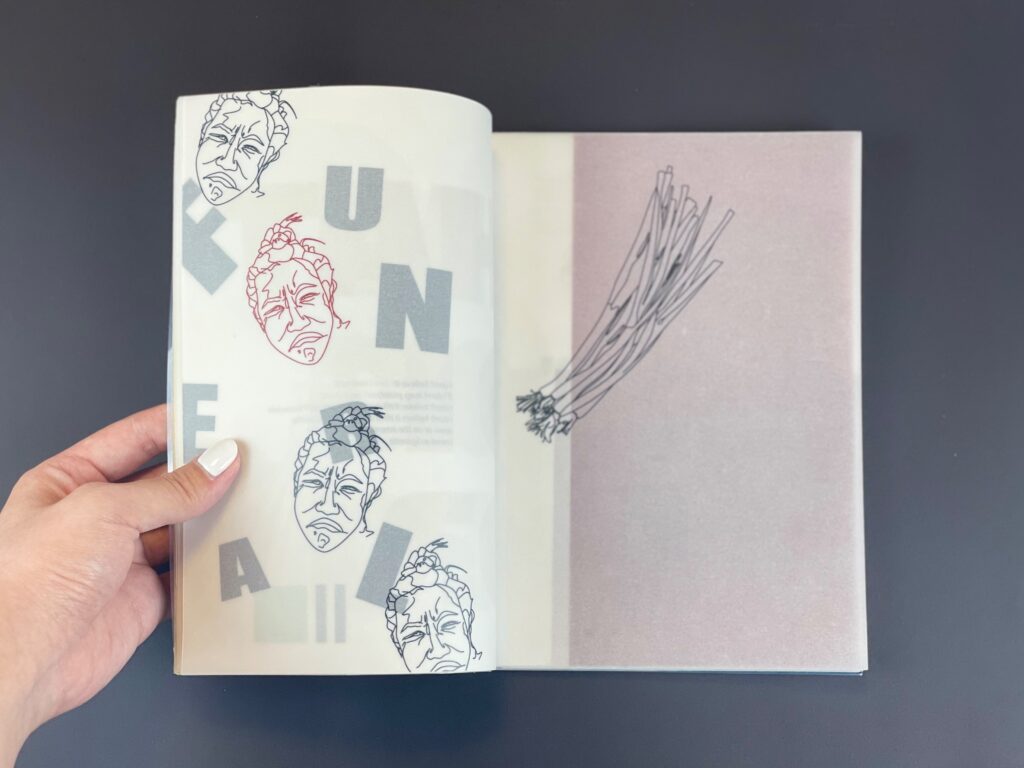

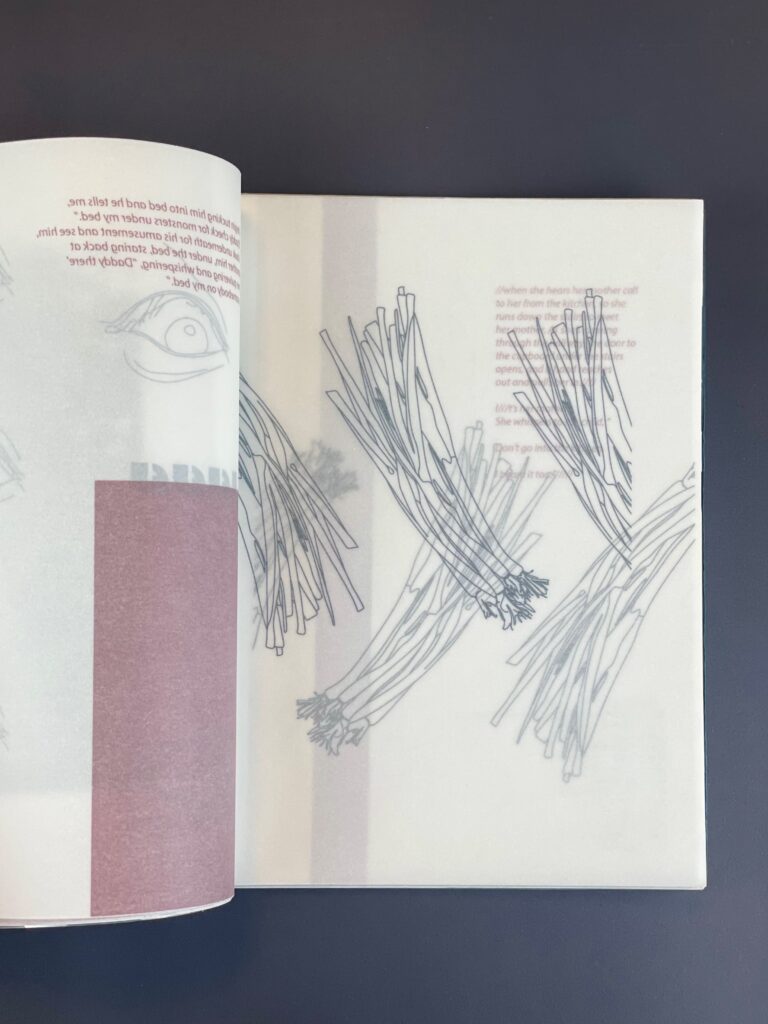

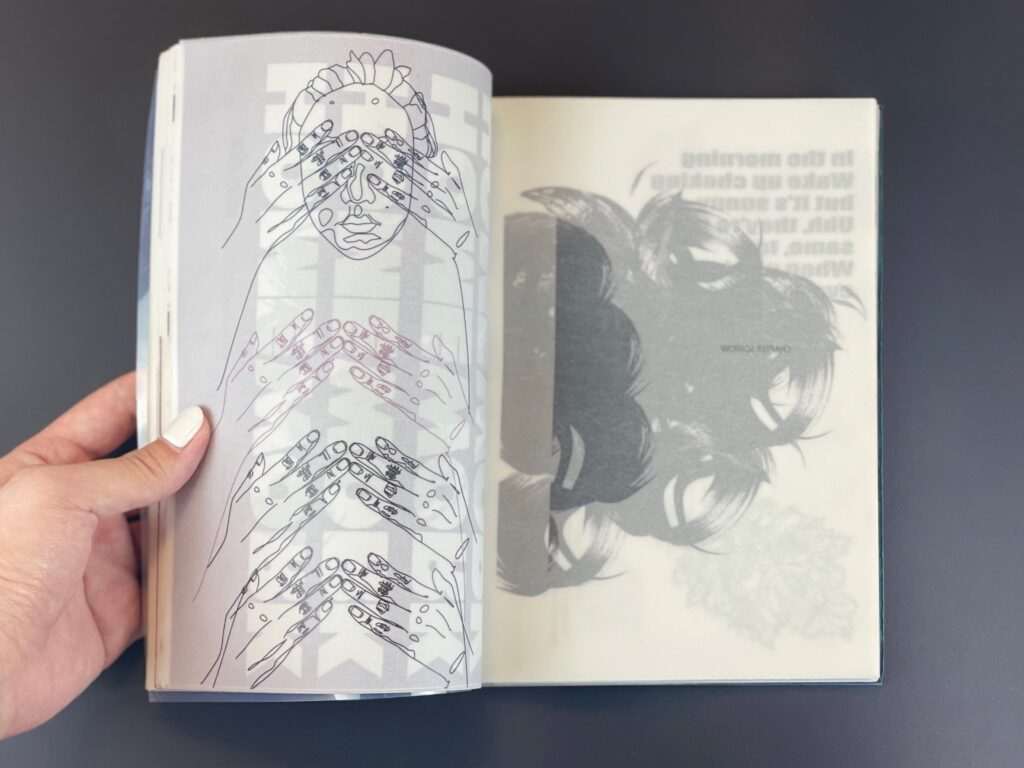

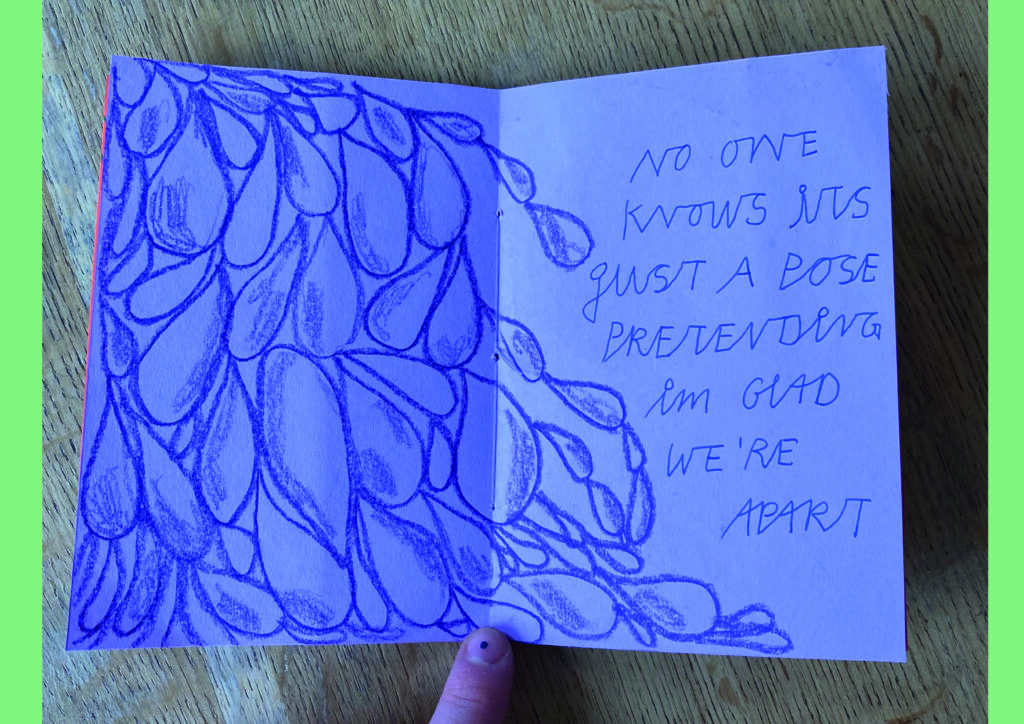

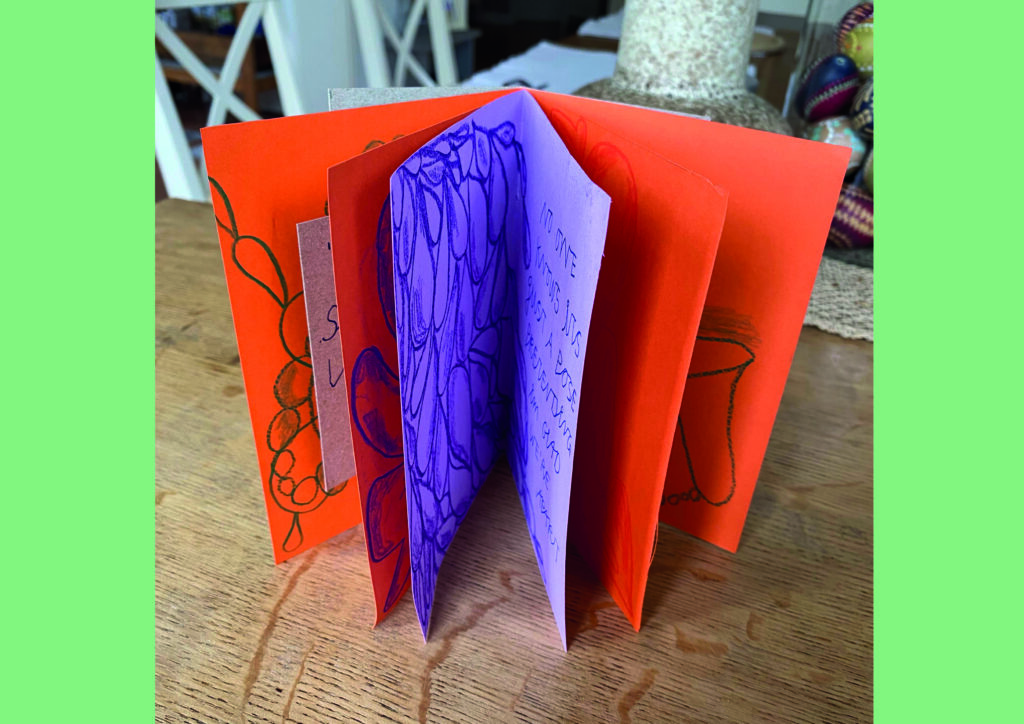

Ich habe mich mit dem Song »Laughing on the outside« von Bernadette Carroll in einem illustrierten Zine auseinander gesetzt. In dem Song geht es um eine zerbrochene Liebe, die Sängerin singt dabei immer wieder, dass sie sehr traurig darüber ist und die Person immer noch liebt, dies jedoch nicht zeigt. Der prägnante Refrain des Liedes lautet deshalb »Laughing on the outside, crying on the inside, cause i am so in love with you«.

Mir geht es bei der Bearbeitung des Songs nicht um den Fakt des Liebeskummers, sondern um die Zeile, dass sie äußerlich lacht, innerlich aber weint. Gepaart mit einer eher fröhlich, warmen Melodie bekommt das Lied für mich einen ironischen Unterton. Ich wollte deshalb den Song als Ausgangspunkt nehmen, um die Zeile »Laughing on the outside, crying on the inside« in einem Zine zu verarbeiten. Dabei geht es mir eher um das Gefühl, die diese Zeile gepaart mit der Melodie auslöst. Es ist etwas sehr echtes und menschliches daran. Beim Illustrieren ging es mir um Situationen, in denen man gern weinen würde, aus Frust, aus Trauer, aus Wut, aus Stress oder einfach nur so, es aber nicht kann.

Entstanden sind Illustrationen einer Gestalt, die all die Tränen in sich trägt, sie aber nicht rauslassen kann oder möchte.

Mmm, mmm

Mmm

I’m laughing on the outside

Crying on the inside

‘Cause I’m so in love with you

They see me night and daytime

Having such a gay time

They don’t know what I go through

I’m laughing on the outside

Crying on the inside

‘Cause I’m still in love with you

No one knows it’s just a pose

Pretending I’m glad we’re apart

But when I cry, my eyes are dry

The tears are in my heart, oh

My darling, can’t we make up?

Ever since our breakup

Make-believe is all I do

I’m laughing on the outside

Crying on the inside

‘Cause I’m so in love with you

Mmm, mmm

Mmm

I’m laughing on the outside

Crying on the inside

Laughing on the outside, Bernadette Carroll, 1962, Musik/Text: Ben Raleigh, Bernie Wayne: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laughing_on_the_Outside_(Crying_on_the_Inside)

By Xiuyi Wu and Yumiko Mita

Crying Culture in CHINA

In China, crying in front of others has generally been seen as shameful. East Asian society as a whole, including Chinese culture, prefers implicitly expressed emotions. However, many people in China view crying as a privilege for women because there are some circumstances in which it is understandable. This phenomena may then be thoroughly examined, and we will discover

that this exemption does not represent preferential treatment for women.

哭嫁 (Crying Marriage):

Crying marriage is an ancient Chinese wedding custom, now common in some remote areas of rural southern China, in which the bride performs a ritual crying at the time of her wedding. Depending on regional customs, crying usually begins about a month before the wedding, when the bride begins to cry and friends and relatives will weep along with her. It is said that the bride is considered unlucky and even condemned by the public if she does not cry.

Lyrics in Crying: The Sadness of Separation

In some rural communities, a married daughter is compared to spilled water, and it is shameful for her to go back to her mother’s family after her marriage. Therefore, once these ladies get married, it is quite difficult for them to see their parents, relatives, and childhood friends.

Complaint against Marriage

In the past, women did not have enough liberty to choose their spouses, and a lot of marriages were arranged by the parents of the bride and groom. It was incredibly frightening to get married to someone you had never met, so it was crucial to express displeasure with this convention and complaints against society in the lyrics of Cry.

Overview

East Asian social anthropologist Choi Kilsong writes in his book, Cultural Anthropology of Crying (哭きの文化人類学), that Hakka (,客家, Chinese ethnic group) women are largely uneducated and that Hakka society is utterly patriarchal and male-centered. It is stated that women only cry to show their emotions on the seldom occasions of weddings and funerals, and that this was the only occasion where they had the freedom to express their emotions. At village gatherings, women are not allowed to speak. Even when elder women speak up, their opinions are rarely taken seriously.

Freedom to cry

Although most developed regions of China have abandoned this tradition, women have always faced varied degrees of inequality in both life and the workplace due to patriarchal society. Whether being forced to cry, or having the privilege of crying because it is seen as vulnerable are something Chinese women want to have.

Crying Culture in JAPAN

Data from the International Study on Adult Crying suggest that, of the 37 nationalities polled, the Japanese are among the least likely to cry. (Americans, by contrast, are among the most likely.)

“Hiding one’s anger and sadness is considered a virtue in Japanese culture,” a Japanese psychiatrist told the newspaper Chunichi Shimbun in 2013.

涙活 (Rui-Katsu):

It’s safe to say we all have much to cry about these days. People are encouraging one another to express mental distress: Even leaders are crying in public. And that’s OK: Crying can be really, really good for you. And that’s the message that Hidefumi Yoshida, a self-described tears teacher, is out to share. He holds workshops across Japan, where he helps grown-ups learn to cry. Whether it’s breaking the stigma around crying out of grief or simply learning to weep for better mental health, it’s a lesson we all could probably embrace a little more right now.

E.g. The Man Teaching Japan to Cry

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ih1l-FR508o&ab_channel=BBCReel

Culturally Appropriate Crying: Gatherings

When one person starts crying, it is a cue for others to cry. This may be due to peer pressure, or to practice homogeneity. People are usually expected to cry when there is a celebration (e.g. Birthday) with alcohol, or when there is a touching moment (e.g. baseball event).

“Cry-Baby”

Women are expected to cry more than men. The gender stereotype that Japanese women are “cry-babies” and emotional are ingrained. Thus, men expect women to cry at any inconvenience that may arise. This is translated to the anime culture as well.

Overview

● Japanese people are most unlikely to express mental distress

● “Hiding one’s anger and sadness is considered a virtue in Japanese culture”

● Tear teacher, Hidefumi Yoshida, started a movement called “Rui-katsu” (Tear Activity) that encourages people to cry

● While expressing distress or strong emotions are uncommon, Japanese people tend to express their true emotions at gatherings that involve alcohol.

● There are also cultural expectations that when one starts to cry, others join in. Women are expected to cry more than men.

CONCLUSION

● While there are differences, China and Japan are both repressive when it comes to expressing emotions. Therefore, many people suffer from mental health issues.

● Crying could be the best practice to regain health, balance in life, especially when our lifestyles have vastly changed and become limited during COVID-19.

● Letting out emotions should not be a taboo; rather encouraged. People should be free to express themselves regardless of societal pressure.

why do we cry?

why are we looking up images of crying?

…..cry, cry, cry……

…..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry……

…..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry……

…..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry……

…..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry………..cry, cry, cry……

…..cry, cry, cry……and cry again.

Book recommendation:

James Elkins: Pictures and Tears. A History of People Who Have Cried in Front of Paintings, Routledge, 2001, https://jameselkins.com/pictures-and-tears/.

Book has two parts:

Art

The first part deals with the works of Sargent, Regnault, Picasso, Rothko and others on their history and importance and examines the states of people who cried in front of a painting. How to make the audience cry and whether education and familiarity with art have an effect on crying or not

Tears

The second part begins with an overview of the opinions of thinkers on crying. And then it shows how in the contemporary world shedding tears in front of a work of art has become a wrong thing. The specific audience considers the art of shedding tears as a form of weakness, or is so caught up in the history of the work that it is meaningless for them to see passion. Elkins says that he has suffered from the same problem and his understanding of art history does not allow him to fully face the work. This thinking has also expanded to the general audience and it seems that art should be viewed without much excitement.

Interestingly, most of the academics who had a tearful memory asked not to be named.

Public performance, Chemnitz, Jan, 2022

Rand Ibrahim

Photography: Leila Keivan

Could a person carry all the grief in the world?

Is that an exaggeration? An overrated dramatic scene?

One day you read in the news: a gang of rats ate an infant’s face

Then you look to the corner of the street and you see a child kicking a dog until he breaks every little rip in his chest.

“Women are still raped and dumped in trash containers”.

On another day, you can extract colorful fragments out of the belly of a smelly dead fish with rotten eyes, which was in the market for people to buy and eat.

There are many reasons to make you cry and burden you with grief and sorrow, not to mention the personal ones.

Sensitivity is a problem

Where did I learn that from?…

When did I learn that?

Photography: Leila Keivan

You were born sensitive; spend your first years crying over anything that does not suit your moody existence.

Your sensitivity contracts while you observe the behaviour of the maniac adults around you.

Your little size friends in school, those who were trained better

will make you realise you should preserve and keep your tears to yourself, just in case you want to survive the next day.

This time a kid will hit me and I will not cry,

I will hit back.

This time they will bomb us,

I will not cry.

I will survive.

It keeps going on until you understand, your tears are valuable, you should only shed them when it is necessary. I will save my tears for the worthy but I am thirty-years old now, and my tears cannot stop running metaphorically.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1pxxmYGqEmFICI2XI5GPL8GKErZY9168m/view?usp=sharing

Menschen weinen als Reaktion auf eine Krise, die das eigene Körpersystem verwirrt und zerrüttet. Ein Prozess des Druckablasses und die Suche nach Sicherheit und Halt wird durch den verletzlichen Organismus eingeleitet. Genauer beginnt die fleischliche Oberfläche zu bröckeln, damit die Tränen die zarten emotionalen Samen des Menschen bewässern können. Eine Pflanzen-Menschen-Hybrid-Metaphorik baut sich auf, die nicht von ungefähr kommt. Schließlich scheint das rhetorische Potenzial enorm, das Tränen der Pflanzen im Prozess der Guttation zu erkennen.

Guttation ist ein Notfallmechanismus von Pflanzen, die sich in Lebensräumen aufhalten, wo eine zu starke Luftfeuchtigkeit vorherrscht, sodass es unmöglich ist, zu transpirieren. Somit kann der Vorgang – zum Weinen analog – als Krisenschutzhebel verstanden werden, der statt Wasserdampf Wasser durch die Blattenden absondert. Dieses Wasser perlt in Tropfenform vom Blatt wie die Träne über die Wange. Die Guttation scheint auch seinen Namen von dieser Erscheinung zu haben, da es sich vom französischen „la goutte“, zu Deutsch „der Tropfen“, ableitet.

Das, was in Tropfenform ausgeschieden wird, nennt sich Xylemsaft. Bei diesem handelt es sich um Guttationsflüssigkeit bestehend aus Phytohormonen, die in Wasser gelöst von den Wurzeln über den Spross durch die Hydathoden an den Blättern herausgedrückt werden. Phytohormone werden auch umgangssprachlich „Pflanzenhormone“ genannt und sind wie beim Menschen für die Regulierung der Entwicklung und des Wachstums der Pflanze zuständig. Nennenswerte Beispiel hierfür sind Florigen oder Cytokinin. Bei den Hydathoden handelt es sich um Wasserspalten, über die die Guttationsflüssigkeit durch Wurzeldruck an die Umwelt abgegeben wird, um den Wasserstrom und Mineralienaustausch aufrechtzuerhalten.

Folglich kann die Guttation als Kompensationsstrategie mancher Pflanzen begriffen werden, die mit sich führt, von einem inneren Druck geformte „Tränen“ nach außen zu pressen, wenn die Umgebung eine luftüberfeuchte Krisensituation herbeiführt (anders zu den von außen gebildeten Tautropfen). Neben den physischen Analogien, die zwischen menschlichen und pflanzlichen Tränen möglich sind herzustellen, wie z.B. die Tropfenform oder die Ausscheidung in Wasser gelöster Salze und Mineralien, eignen sich metaphorische Parallelen besser für die eigene

CRYING REFLECTION.

So wie wir schnell Gesichter in bestimmten Strukturen erkennen, äußern wir scheinbar schnell unsere Vermutung, dass das Tropfen eines Wesens oder gar einer Sache an den Prozess des Tränens erinnert. Unsere empathische Fähigkeit motiviert diesen Vergleich, da wir nicht wirklich schätzen, was tatsächlich der Grund für das bildähnliche Tränen von Hundeaugen oder das Harzen von Baumrinde sein soll, sondern unseren eigenen Moment des Weinens darin sehen. Vielleicht gerade, weil wir keine genaue Antwort darauf haben, warum wir manchmal weinen. Dabei kommt der Gedanke auf, dass durch die Guttation eine simple, aber wesentliche Begründung geboten wird. Es geht hierbei um die Aufrechterhaltung des verletzlichen Systems einer zum Überleben getriebenen Lebewesen – ob Pflanze oder Mensch. Gerade im Moment des Zusammenbruchs können Tränen helfen, den Druck aus dem inneren mit dem Druck von außen wieder in Balance zu bringen bis man aufhört, Salzwasser auszustoßen, um nicht auszutrocknen.

Ein Tränenkreislauf wird hergestellt.

Der zyklische Ablass und Aufnahme von Druck soll (scheinbar im Sinne eigener poetischer Ansprüche) als Ventil dienen, das Wasser, wie den Xylemsaft, nicht zu eliminieren, sondern erst als flüssige Tropfen abzugeben, die verdampfen, um folglich ein weiteren Organismus in den Zustand des reinigenden Weinens zu bringen. Wiederum erhöht sich der Wassergehalt in dessen Umgebungsraum. Der Wasserdampf wird absorbiert und kann das Überlaufen des Körpers mit Tränen erneut begünstigen. Tränen werden zu Tränendampf und der Kreislauf wird fortgefahren. Zusammen im selben Raum zu sein, der durch eigenes Weinen luftfeuchter wird, stellt einen eigens bezeichneten „Pumpraum der Katharsis“ dar, in dem sich die Wesen im Mit- oder Gegeneinander anweinen.

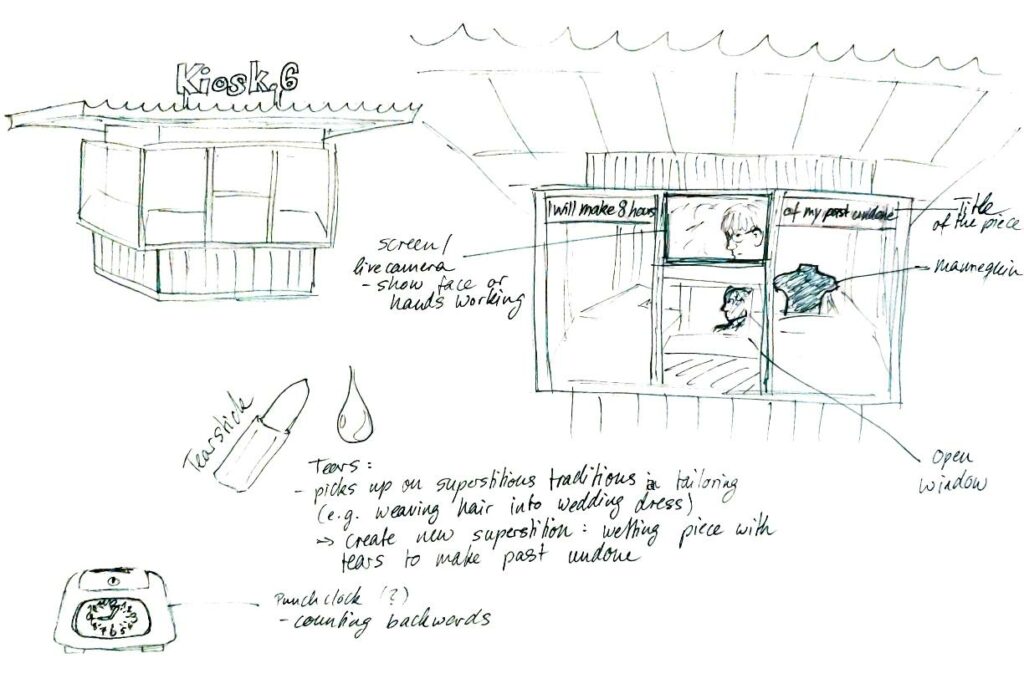

The aim of this project is to create a performance that will last for eight hours – the normalized span of a working day (at least in Western-European conceptions of employment). The performance refers to my personal past, working as a tailor for several studios and workshops.

I will invest eight hours of labor in undoing my own work by taking apart a jacket that I have made myself (within more than 60 hours of handcrafting).

The performance should take place in a shop window.

The performance will take place during summaery 2023.

The project poses questions of what it takes to undo or erase – what can possibly be undone through the process of taking apart and what new things, objects, ideas, feelings, memories, and values emerge from it?

Is it possible to undo work? And with it erase passed time? Ultimately, will it be possible to undo time?

+ The performance will happen inside Kiosk.6 at Sophienstiftplatz, Weimar.

The performance will take 8 hours. Within the 8 hours I will take apart a jacket that I have made myself during my apprenticeship stitch by stitch.

+ With me in the Kiosk there will be the jacket, a chair, the tools I need to take it apart, an empty mannequin, a punchclock and a camera. The singled out pieces of the jacket will fill up the window displays bit by bit.

The camera will be directed at my face, covered in tears, or at my hands by turns.

+ The front window of the kiosk will be open to enable interaction with passers-by.

Above the window there will be a screen showing what the live-camera captures.

Next to the screen the title of the performance is displayed.

+ Every hour (starting on hour 0) I will punch the punchclock, that is programmed to count backwards. I will also use a tear-stick to make my lacrimal sacs produce tears.

+ The performance ends when the 8 hours have passed. By the end all pieces of the jacket shall be detached from each other.

In tailoring, like in many artisan traditions, there are a lot of superstitions intertwined with the craft. They mostly connect with abjects of the body of the artisan, produced while working on a piece. For example: In Germany, when making a wedding dress, a drop of blood should be placed somewhere at the inlay – which is supposed to bring good luck and help for a happy marriage (it also used to symbolize bloodline and a mother’s grieve, as the mother of a bride was supposed to sew her wedding dress). In France, unmarried embroiderers would sew in one of their own hair into a wedding dress, in order to be the next one to marry.

I decided to create a new superstitious tradition, making use of my tears. By crying while opening the seams of my jacket, I can make the past undone.

At the same time, the meanings of the tears – like those of the drop of blood – are manifold. They symbolize superstition, but they could also flow because of grieve, trauma, fear, melancholy, or relieve. They catalyze negative emotions and wash them out.

The term “swallowing one’s tears (back)” is often used to describe someone suppressing their grief or despair, stopping themselves from crying. The expression seems to float somewhere between a figure of speech and a literal description of a physiological process. However, in most dictionaries, no entry can be found.

Here are some examples on possible usecases of this expression (translated from German):

“James de Malplaquet sang to it as if he had to swallow his tears, with a gentle vibrato in his voice, a glass of whisky or red wine in his hand nearly all the time (…) and paid homage to such beautiful despair that one felt the desire to drown oneself in a barrel of ale in the cellar of a British pub that very night.” (Tagesspiegel, Oliver Dietrich, 20.01.2012)

“Sharma apologised before the plenary with his head bowed, paused, had to swallow his tears. Shortly afterwards, the watered-down Glasgow Pact was adopted.” (taz, Susanne Schwarz, 12.12.2022)

“This time, however, Stanisic has to swallow tears for once, which make his voice brittle. ‘That’s how it is when you work with memory,’ he says, ‘eventually it gets you.'” (Süddeutsche Zeitung, Karin Janker, 14.06.2019)

Similar semantic constellations also exist in other languages than just German and English, for example, svälja gråten in Swedish, polykat slzy in Czech, or inghiottire le lacrime in Italian. In other words: We’re probably onto something.

However, in terms of its physiological content, the phenomenon of swallowing tears hardly appears to be a subject of scientific interest. This could indicate that it is actually more of a metaphorical construction than a physiological process. Yet, a brief study of the process of crying itself certainly shows the possibility of a literal interpretation, for tears are formed in the lacrimal glands and then flow through the tear ducts into the nasal cavity. This in turn is connected to the pharynx, so that it is indeed possible to swallow one’s own tears very naturally (alongside the mucus that also forms in the nose when weeping).

That swallowing (back) one’s tears is an actual thing might be also supported by the fact that any advice to stop unwanted crying often mentions intentional swallowing. This is where the proverbial “lump in the throat” comes in. It occurs because emotional crying opens the muscle at the back of the throat, called the glottis. Crying tries to keep the glottis open while swallowing, creating the feeling that a lump is forming in the throat. It is advised to drink a sip of water, swallow empty or yawn, which can help the felt lump, and eventually the crying itself, to go away.

The German speaking internet as well as reddit wonder if it is harmful to swallow one’s own tears, but be reassured: This does not seem to be the case.

Metaphorically, or even poetically speaking, the process of swallowing one’s own tears seems significant in that crying per se seems to perform a movement from the individual’s inside to their outside: emotions and the nervous system produce a fluid that makes its way from the interior to exterior parts of the body, to the visible and thus to the social, when tears run down the cheeks. Swallowing tears reverses this process: The movement into the outside is thwarted and diverted back into the inside, the attempt to make and become visible is prevented and the social potential of crying, the receiving of support and help from others, is made impossible.

But: perhaps you’re just saving them for another day?

Was geschieht in uns wenn wir weinen? Innen- und Aussenraum driften auseinander, Gedanken kreisen, Flashbacks, schmerzhafte Erinnerungen …

Wie klingt das? Ein Entwurf: 🎧 https://on.soundcloud.com/b37nG

Die Sampels dieser kurzen Komposition entstammen “Adagio for Strings” von Samuel Barber, gespielt vom London Philharmonic Orchestra & David Perry.

Since I came to create images with Midjourney, I’ve been trying to test the limits of this AI. Let’s leave all the controversies aside for a moment to use it as tool, to reflect on the inevitable bias of this platform.

Trying to escape from surreal intergalactic scenes and the fashion images I’ve been scrolling on my Instagram, I was looking for subjects that were not just hard to materialise but also hard to imagine – at least in my limited mind.

Back in Brazil, I always wanted to do a photoshoot of men crying but as I didn’t want to use models – and we do have a very macho culture – I couldn’t even imagine being successful with this project. This then felt like a good prompt: Man crying.

Let’s start with the referential being. If you ever tried AI you might have noticed how unlikely it is to get a non-white subject if you don’t explicitly describe a body that it not white. This annoyed me in every trial, always getting a white male if I’d just typed “man”.

Now think about your own visual culture. Films, photographs, videoclips – how many times have you watched a black or latin man crying? What was the context? How was the facial expressions? Smooth? Desperate?

Then I wanted to check what a Colombian man looks like on Midjourney. The prompt “red eyes” was a trap, I know.

As a human being we know that red eyes could state that one has cried for a long time even if there’s not apparent tears on their eyes anymore. But that’s too subtle to prompt.

Instead of getting red iris, as I would assume I would get, the red came mostly as bruises and the smooth crying expressions I was looking for never came out. This reminded me that the few times I saw a man crying (not in person) were in catastrophic scenarios.

Reading “The Will To Change” by Bell Hooks I felt like getting deeper with understanding how do I deal with male feelings, therefore, male tears. Being daughter of a father who cries A LOT, my experience with male tears was pretty singular comparing to the general visual culture I had and I confess it didn’t make me better dealing with them.

But I know that images can help us to empathise and, after this exercise, I may go back to the “crying men” project to at least help me to enlarge my own visual culture.

In the brief time between Christmas and the New Year, everything seems dead. In the northern Hemisphere, at least, it’s cold, wintery and grey, everyone has gone home for the holidays and the streets of student towns like Weimar and Jena are suddenly eerily empty. What can you do if you’re craving warmth and life during this week? Well, I personally decided to go to the botanical garden in Jena to look at some plants, and ended up thinking a lot about crying, tears, and what it means for us as humans to observe nature and project our own baggage onto it.

Ah, plants. They’re all around! On the street, growing between cobblestones, hanging from bookshelves in messy WG-rooms… They’ve been around a long time, obviously. As have we. And it’s safe to assume that plants have always had a special meaning for the people that interact with them; from houseplants to the trees in your favorite park, they are something like silent companions, a reminder that not everything was made by human hands, and that there are things that grow and change without us, and live on after we’re dead.

Crying is also a fundamental part of the human experience, and sadness is something we like to project onto other beings and things, be that out of a desire to connect or just out of our self-centered view of the world. I recognize sad faces in power outlets, in air bubbles in slices of bread, and, of course, I recognized tears and “sadness” in the plants at the botanical garden in Jena. I saw heart-shaped leaves and droopy flowers, and thought of how plants and tears are connected on so many levels, which led me to my theme of Chlorophyll Tears.

A common first association for us is the classic image of the Weeping Willow, a tree that literally has the word “weeping” in its name. Its sad, long, limp, drooping branches grow downwards, as if it just couldn’t be bothered to try anymore (we all know that feeling). What I didn’t know, is that there is an entire category of trees that also have the word “weeping” in their names, like the Weeping Flowering Apricot and the Weeping Atlas Cedar, that also share these same characteristics. They can also be found in graveyards, which brings me to the connection between plants and death, and, by extension, grieving.

I realized that there are a lot of examples in fiction of characters in stories who die and are buried under trees. In the original story of Cinderella, for example, her mother is buried under a Weeping Willow; in the new stop-motion adaptation of Pinocchio, Gepetto’s human son is also buried, and a tree is planted on his grave. In Sleepy Hollow, there is literally a tree that is called “The Tree of the Dead”, under which the Horseman had been buried many years before. These are just some examples, but it is definitely something we see often. In this way, some trees become a “designated crying place”, a place to sit in the shade and grieve the loss of a loved one.

It also seems as though the tree symbolizes a continuation of the life the person has lived; in a sense, they “live on” through this plant that now nourishes itself from the decomposing corpse. In their project, “Capsule Mundi”, designers Raoul Bretzel and Anna Citelli created a burial method that has exactly this intention; a type of egg-shaped “pod” where you could be buried, onto which a new tree could attach its roots and grow in your absence. It’s also hard to ignore the presence of flowers at funerals and memorials, as well as stories like that of the “forget-me-not”, which reference grief and attribute the blue color of their petals to tears. Death is every living thing’s final destination (except for maybe that immortal Turritopsis dohrnii jellyfish). Therefore, it’s somehow poetic that the plant kingdom also takes part in our human rituals, provides comfort and brings beauty to the sad happenings of life. In many ways, death connects us all, regardless of our taxonomy.

But enough about us, what about them? Do plants feel pain? Do they grieve? Cry, even? I suppose that’s what we want to know about every living thing, or sometimes even non-living thing. Typical humans, projecting their own feelings onto completely nonsensical contexts. I, for one, have been googling for as long as the internet has been a thing, always trying to find out if my pets could feel the same things I could, if they cried too (I was a crying enthusiast as a child, and, honestly, still am). I never had my own plants until I started university, and then my thoughts went to them. Do my houseplants get sad? Do the trees in Germany get cold in winter, and cry, just like us, international students from tropical climates?

As it turns out, trees do, in fact, emit ultrasonic sounds (A.K.A. screams?) when they are distressed, for example, when they don’t have enough water. The xylems that carry fluids from the roots to the leaves start picking up air particles when there is no water left, and after a certain point this can be deadly. There are scientific projects in motion that aim to pick up on these frequencies that we cannot hear, so as to quickly water trees at risk of dehydration.

These ultrasonic sounds are, of course, sounds, however, could they be categorized as crying? In a way, the dehydrated trees are suffering, and are expressing their suffering. It’s a natural occurrence; they can’t control the sounds they make. They react to a circumstance that brings them pain, and so do we, when we cry out of sadness. We also don’t always have the intention of crying; we sometimes also cry alone, we make unintelligible noises, too. In that sense, I suppose trees do cry… And we can’t hear them.

So as an exercise, I’d like to suggest you check up on your houseplants, and on the trees you see on your way to work or class; offer them a kind word, a gentle pat, a cup of water, and tell them it’s ok to cry; if you’re a crybaby like me, they’ve probably seen you cry a lot too.

Weinen verläuft nicht konstant linear, es lässt fließen, was mehrschichtig ist. Es handelt sich dabei nicht nur um eine einzige Art von emotionalen Tränen, sondern hunderten, die durch die verschiedensten Verformungsstationen laufen. Viele davon werden zigmal hinterfragt, ob sie ausreichend aufrichtig und angemessen sind, damit sie fließen dürfen. Danach fließen sie. Und dann wird nochmal hinterfragt. Auch gibt es welche, die kommen durch ein kleines Lächeln zustande. Sie quellen mit den anderen Tränen der Trauer, des Frusts, der Überforderung zusammen über, weil man ja irgendwie die kleinlich wirkenden Impulse der netten Erleichterung im Angesicht der grundverwirrenden Krise auch noch rausschießen muss.

Das Weinwasser füllt meinen Raum. Je mehr an Niederschlag fällt und sich an Hitze entfaltet, desto tropischer wird es. Ein Klima, worauf meine Pflanze reagiert. Kurz doch: Sie reagiert nicht auf das Klima, sondern ursprünglich auf meine Tränen. Vielleicht weine ich nicht (nur) für mich, sondern auch für meine Pflanze. Bedauernswert, aber warum sollte ich sonst für mich weinen? Sie versucht, ihr eigenes Wasser loszuwerden – wie ich meines – zu transpirieren, damit sie sich versorgt. So muss es bedeuten, dass ich für mich weine, damit ich mich selbst umsorge, wenn kein anderer Mensch mit mir weint oder mir Aufmerksamkeit schenkt. Aufmerksamkeit kommt nicht immer nur von Menschen. Alles kann eine Projektionsfläche fürs eigene Geweine sein – Worte, Blicke, Ideen, Erinnerungen, Träume, Nostalgien, Infantilisierungen, Dystopien, Verwirrungen, Besuche, Haustiere oder eben auch Pflanzen. Egal, ob die Pflanze über mich denkt oder sie überhaupt nicht denkt, weil sie gerade und für immer einfach nicht die Nerven hat, sie muss genauso die Situation kompensieren, wie ich es tue. Ich stecke sie an und der Gedanke darüber, dass sie von mir angesteckt wird, infiziert mich weiter.

Es wird immer feuchter und stickiger im Raum. Ein Druck entsteht, der mich ans Bett klammert und mich weiter heulen lässt. Für sie reicht es nicht mehr aus, Wasserdampf auszustoßen, es tropft nun bei ihr. Durch meinen fetten Tränenfilm hindurch wie bei einer Brille mit zu starken Linsen blicke ich auf die Blätter der Pflanze mit ihren Zacken. Sie sehen aus wie Wimpern und schlagen sich schwer, die dicken Tropfen, die sie festhalten, auch wirklich nicht loszulassen.

Aber das Blatt hält es nicht aus, meine Lider schließen sich, der Tropfen fällt.

Obwohl sie nur zusätzlich Wasser verliert, will ich darin etwas sehen – ein Zeichen, eine mystische Offenbarung, irgendetwas, was auf mich reagiert, es mir gleichtut und mir mehr gibt. Ich benetze den Raum nicht nur mit immer mehr Tränensekret, sondern lasse wimmernde Geräusche hineinpoltern – auch hier, schätze ich, absorbiert meine Pflanze als würde sie Musik hören … ich weiß nicht wirklich, was sie davon hält. Hinterlässt sie eine Salzkruste auf ihrem Blatt, so hinterlasse ich das auch. Es muss trocknen und salzig schmecken, damit ich dann mit feuchter Tinte bittersüße Wörter schreiben kann.

Die Pflanze umsorgt sich somit in einer Krisensituation, dabei denke ich, dasselbe auch zu tun. Dass trotz momentanen Zerbrechens, ich danach frischer und reiner bin. Voller neuer Nährstoffe. Es greifen Momente der Realisierung, dass das nicht für immer ist, sie aufhört mit dem, was sie tut, und ich dennoch weiter weine – wieder allein gelassen zu werden. Vielleicht brauche ich länger als sie. Manchmal halte ich mein Weinen für lächerlich, aber ich lasse es zu, damit ich etwas habe, um danach zu lachen. Wer darf bewerten, ob meine Tränen echt sind oder ob ich weinen darf, wenn ich‘s doch selbst nicht weiß?

Und schließlich hörte ich auf zu weinen.

Was es auch immer war, was sich nun zum Fluss ergab,

hält sich nun als Nebel bereit,

die Gefühlssphären anderer Weinender zu bewandern

Befeuchtend Verklumpend Erstickend

damit Nächste sie im hellen Liegen absorbieren,

wartend bis ihre Tränensuppen versiegen,

um den Grund zu sehen.

von Jeremy Wiener

I finally broke down crying a few nights ago, after what seems like a lifetime of feeling emotionless. I actually wrote what exactly happened, like what triggered it – but on a second thought you probably don’t need to know that.

This is me feeling energized and amazing after an entire night of crying.

imagine two

who

love to play

setting on fire

what’s on their way

imagine two

who

love to fight

taking no prisoners

as they burn bright

imagine two

who

don’t pull back

when the pain peaks

and there’s blood on the tracks

imagine two

tears on my pillow

BK January 2021

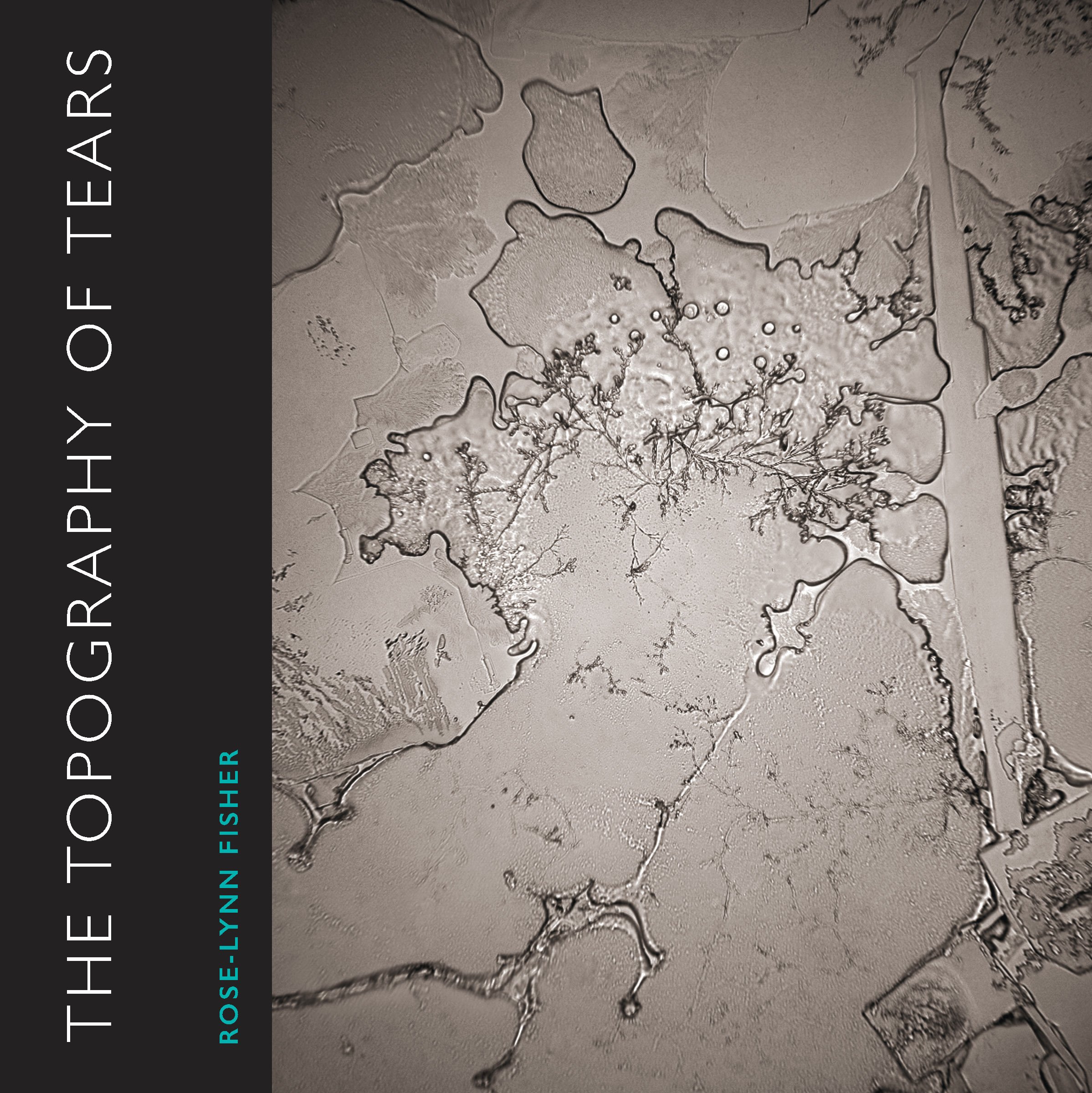

“The Topography of Tears” von Rose-Lynn Fisher und “Imaginarium of Tears” von Maurice Mikkers.

»The Topography of Tears« zeigt Nahaufnahmen von Tränen verschiedenster Ursprünge, angefangen bei emotionalen Tränen, wie Trauer oder Freude, bis hin zu Reflex-Tränen, wie sie beim Zwiebelschneiden oder dem ungeschützten Blick in die Sonne entstehen. Seit 2008 arbeitete die US-Fotografin und Künstlerin Rose-Lynn Fisher diesem Projekt, das 2017 als Publikation bei Bellevue Literary Press erschien.

“The Topography of Tears” versammelt die Bilder von Tränen verschiedener Ursprünge, angefangen bei emotionalen Tränen, wie Trauer, Verzweiflung, Wut oder Freude, bis hin zu Reflex-Tränen, wie sie beim Zwiebelschneiden oder dem ungeschützten Blick in die Sonne entstehen. Rose-Lynn Fisher sammelt diese Tränen und überträgt diese auf Trägergläser. Mit Hilfe eines Lichtmikroskops aus den 1970er Jahren betrachtet sie die entstehenden Ansichten der Tränen und nimmt diese mit einer Mikroskop-Kamera auf.

“The Topography of Tears” versammelt die Bilder von Tränen verschiedener Ursprünge, angefangen bei emotionalen Tränen, wie Trauer, Verzweiflung, Wut oder Freude, bis hin zu Reflex-Tränen, wie sie beim Zwiebelschneiden oder dem ungeschützten Blick in die Sonne entstehen. Rose-Lynn Fisher sammelt diese Tränen und überträgt diese auf Trägergläser. Mit Hilfe eines Lichtmikroskops aus den 1970er Jahren betrachtet sie die entstehenden Ansichten der Tränen und nimmt diese mit einer Mikroskop-Kamera auf.

Das Projekt entwickelte sich aus einem Trauerprozess Fishers heraus. Neugierig über die visuelle Beschaffenheit von Tränen sammelte sie diese und machte sie mithilfe eines Lichtmikroskops und einer damit verbundenen Kamera sichtbar. Dabei arbeitete sie nicht ausschließlich mit den Tränen der Trauer, sondern machte die »unsichtbare Welt ihrer Gefühle sichtbar« (Website Fisher, Üb.d.A.), indem sie Tränen aus verschiedenen Gefühlslagen sammelte, um zu untersuchen, ob sich deren Aussehen unterschied. Sie experimentierte mit Aufnahmesituationen (z.B. luftgetrocknete oder zwischen Deckglas eingeschlossene Tränen), Druckverfahren und Papieren. Ihre Arbeit zeigte, dass jede Träne ein individuelles Aussehen hat, selbst wenn sie das gleiche Gefühl zeigt direkt nacheinander in der selben Situation entstanden ist. Neben einer Sichtbarmachung der Gefühlswelt spricht Rose-Lynn Fisher von Landschaften; individuell, einem Fingerabdruck gleich.

»Although the empirical nature of tears is a composition of water, proteins, minerals, hormones, antibodies and enzymes, the topography of tears revealed to me a momentary landscape, transient as the fingerprint of someone in a dream. This series is like an ephemeral atlas. […] [Tears] are the evidence of our inner life overflowing its boundaries, spilling over into consciousness.«

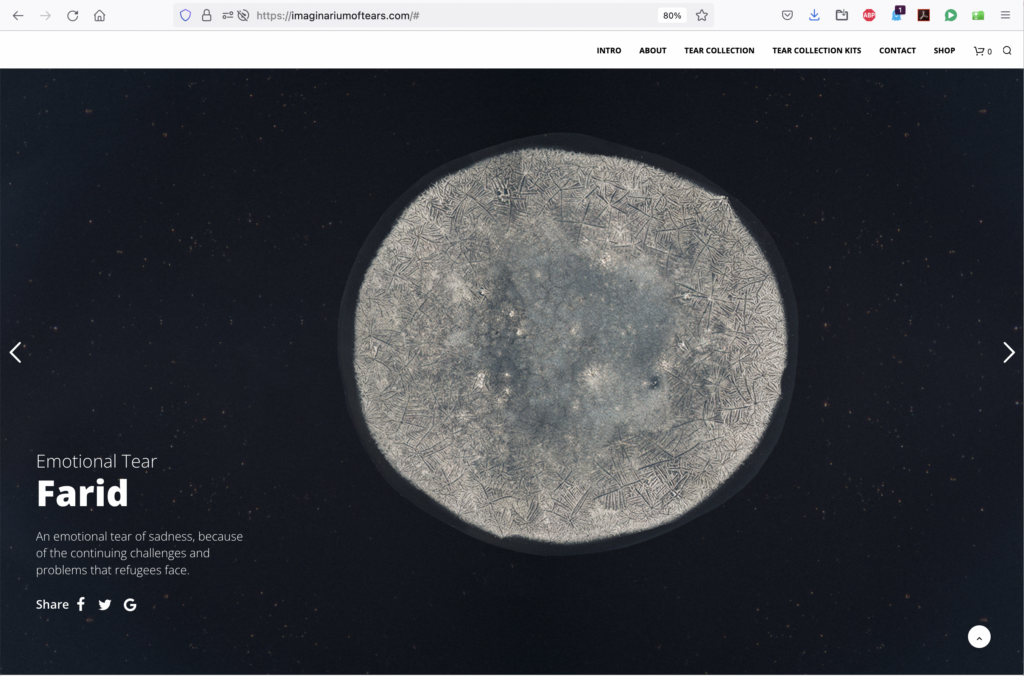

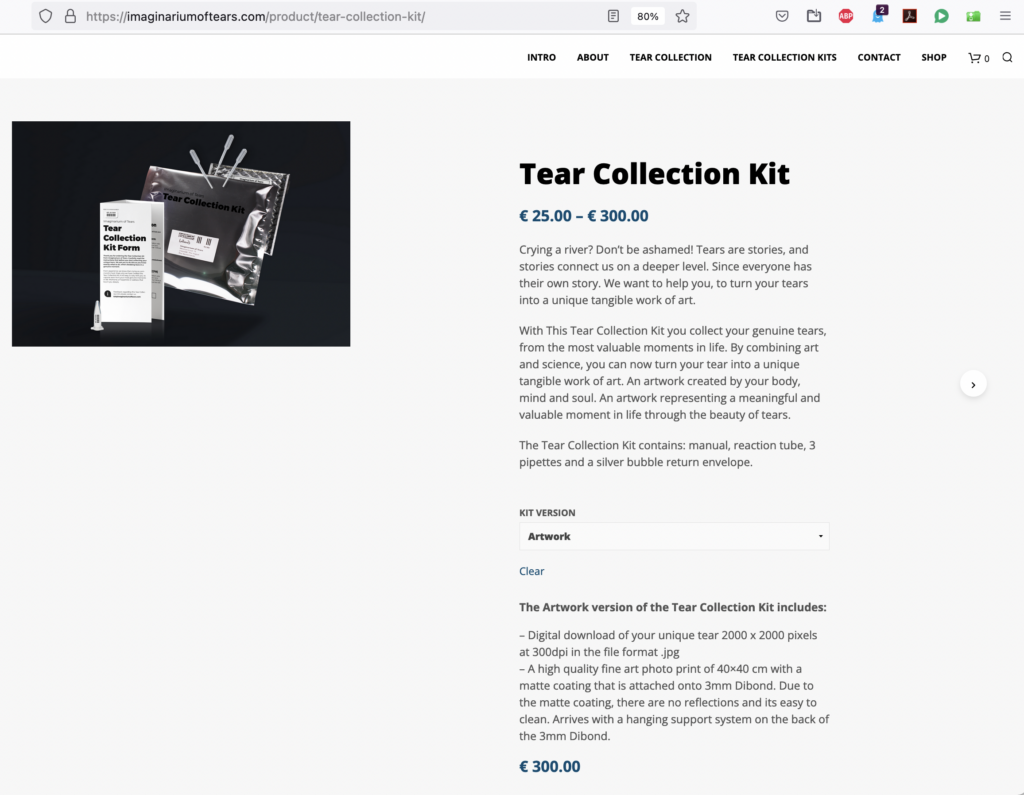

Der niederländische Künstler und Chemie-Laborant Maurice Mikkers begann 2015 mit einem ähnlichen Projekt. In seiner Arbeit verbindet Mikkers Kunst mit Wissenschaft und Technik und bedient sich dabei des Wissens, das er sich während seiner Ausbildung und Arbeit als Laborant, sowie in seinem Kunststudium an der Royal Academy of Art in Den Haag angeeignet hat. Bereits vor seinem 2015 begonnenen und bis heute andauernden Projekt »Imaginarium of Tears« verband er in sogenannten Micrograph-Stories das Mikroskop mit der Fotografie.

Während der Arbeit an einer Micrograph-Story stieß sich Mikkers nach eigenen Angaben im Labor derart stark den Zeh, dass auf Grund des Schmerzes einige Tränen flossen. Reflexartig nahm er eine dieser Tränen mit einer Pipette auf und betrachtete sie unter seinem Mikroskop. Der Anblick faszinierte ihn und sorgte für das Entstehen seines Projekts »Imaginarium of Tears«. Er experimientierte mit verschiedenen Mikroskopen und Aufnahmemodi und entschied sich letztlich für das Dunkelfeldmikroskop – anders als Rose-Lynn Fisher, die ein einfaches Lichtmikroskop nutzte. Durch den schwarzen Hintergrund des Dunkelfeldmikroskops und die Beleuchtung des Objekts wurde sowohl die äußere, runde Form, wie auch die kristalline Struktur der Tränen sichtbar.

Mikkers verbindet die Tränenbildern mit kurzen Sätzen zu den Hintergründen der Tränen und zeigt dies online auf der projekteigenen Website “Imaginarium of Tears“. Er spricht von den besonderen Geschichten der Tränen, die er mit diesen zusammen darstellt. Auf seiner Website tauchen diese besonderen Geschichten jedoch lediglich in ein bis zwei Sätzen auf. Sind ein bis zwei Sätze überhaupt in der Lage, die Besonderheit einer Geschichte zu erzählen? Oder traue ich dem Wort, gerade wenn es wie hier affektappellierend auftaucht, zu wenig zu? Auch Fisher arbeitet mit Text. Sie ordnet über deren Betitelung die Bilder ein (z.B. »After the sun came the tears« 2016 oder »Thankful for exactly this« 2017), ohne den kommunizierten Wunsch, damit eine besondere Geschichte erzählen zu wollen. Vielmehr eröffnen die kurzen Titel im Vergleich zu Mikkers Geschichten einen Raum für Imagination bei Betrachter*innen.

Die visuellen Ergebnisse von Mikkers Arbeit sind hoch ästhetisierte Aufnahmen, die mehr an Dekorationsobjekte als an Kunstwerke erinnern. Dieser Eindruck wird dadurch verstärkt, dass Mikkers seine Arbeit über spezielle Tränen-Kits vermarktet. Bis zu einem Preis von 300€ kann sich jeder ein Tränen-Kit bestellen, eine eigenen Träne sammeln und sich je nach Kit ein eigenes Tränenbild nach Hause schicken lassen. Wie wirkt sich eine solch vermarktende Strategie auf die Wahrnehmung seiner Arbeit aus? Sie bewirkt zunächst eine veränderte Wahrnehmung seiner Arbeit, die anfänglich faszinierend schön erscheint. Skepsis und Unsicherheit begleiten die Wahrnehmung und hinterfragen, wie eine solche Strategie gelesen oder anerkannt werden soll. Spricht sie der künstlerischen Arbeit etwas ab? Wirkt sie sich negativ auf die Wertigkeit der Arbeit aus? Oder ist dies eine Ansicht, die zu sehr das individuelle Kunstwerk in den Mittelpunkt stellt, während Mikkers die Ergebnisse seiner Arbeit jederm zugänglich macht, sofern ersie das nötige Kleingeld besitzt? Es bleibt ein Unbehagen.

Ich betrachte die Tränenbilder Fishers und Mikkers mit einer Faszination für das bis dato Unsichtbare. Doch die durch und durch abgestimmte Hyper-Ästhetik bei Mikkers löst nach kurzer Zeit die Faszination durch ein Abstandnehmen ab. Wofür braucht es einen Hintergrund, der in seiner Optik an das Universum mit Sternen und Planeten erinnert? Im Vergleich dazu sind die Bilder Fishers wesentlich reduzierter. Sie beinhalten keine spezielle Beleuchtung, kein Einrahmen in einen Kontext, um die in Tränen ohnehin enthaltende besondere Ästhetik sichtbar zu machen.

Im Unterschied zu der Künstlerin Rose-Lynn Fisher arbeitet Maurice Mikkers in der Werbebranche. So ist es nicht verwunderlich, dass eine dort inhärenter Vermarktungsstrategie auch seine künstlerische Arbeit begleitet. Während bei Fisher das Interesse für die Sichtbarmachung und ein Vergleichen von verschiedenen Tränenarten die Antriebsfeder war, die sich erst viele Jahre nach Beginn des Projektes in einer Publikation abschloss, beginnt Mikkers relativ zeitnah mit der Vermarktung von Tränenbildern. Da Tränen an unseren Affektapparat appellieren und etwas Grundlegendes sind, das jeder Mensch selber erlebt hat, ist eine Identifizierung, vor allem, wenn sie mit einer eindrucksvollen, und somit zusätzlich die Affekte ansprechenden Ästhetik einhergeht, einfach hergestellt. Werbung appelliert gezielt an Affekte, da durch diese der Absatz für Produkte steigt. Inwiefern spielt dieses Wissen Mikkers bei seiner Arbeit, dessen Präsentation und Vermarktung eine Rolle?

Zusammenfassend bleibt zu sagen, dass beide Projekte in ihrer Unbekanntheit und eigenen Ästhetik mich zunächst sofort angesprochen haben. Doch bereits nach kurzer Zeit setzte Skepsis ein. Während Fisher sich von einem wissenschaftlich, forschenden Ansatz in ihrer Arbeit distanziert, erhofft Mikkers, im Laufe des Projekts detaillierter Aussagen zur Zusammensetzung und Beschaffenheit von Tränen machen zu können; unter anderem auch durch bessere Technik und eine interdisziplinäre Zusammenarbeit. Seit seinem 2015 begonnenen Projekt haben sich die auf seiner Website präsentierten Bilder jedoch nicht verändert. Es ist kein forschender Prozess sichtbar. Vielmehr tauchen Logos diverser Medienunternehmen auf, die darauf verweisen, wo Informationen über das Projekt publiziert worden sind. Wenn es sich um ein forschendes Projekt handelt, sind dann nicht gerade die unterschiedlichen Prozesse, die Zwischenergebnisse von Interesse? Diese finden sich auf der Plattform Medium.com. Dort unterhält Maurice Mikkers einen Blog, auf dem er über sein Forschungsprojekt, die verschiedenen Etappen und Probleme berichtet. Dass die die anfängliche Faszination abgelöste Unbehagen wandelt sich Fragen. Fragen, die nicht darauf anspielen, eine künstlerische Arbeit als gut oder schlecht, als gelungen oder nicht einzuordnen. Maurice Mikkers »Imaginarium of Tears« resultiert in Fragen, die sich neben seiner Arbeit und dessen Inhalten mit dem Kunstmarkt und dessen Mechanismen auseinandersetzen.. Sein Broterwerb im Design hinterlässt Spuren in seiner künstlerischen Arbeit. Sein Tear-Kit ist eine, nicht weiter verwunderliche, kommerzielle Möglichkeit, um Tränen für sein Projekt zu sammeln und dieses gleichzeitig zu finanzieren. Zu schnell stoßen kommerzielle Aspekte in künstlerischen Arbeiten auf Ablehnung. So auch bei mir. Anderseits ist den meisten bewusst, dass es an Möglichkeiten der Finanzierung künstlerischer (Forschungs-) Projekte mangelt und dass die Kommerzialisierung von Anteilen eigener Arbeit eine legitime Möglichkeit ist, die eigene Arbeit finanziell zu ermöglichen. Doch ein Beigeschmack bleibt.

Mikkers und Fisher teilen eine Neugierde für die visuelle Natur der Tränen. Sie teilen Erkenntnisse, die sich durch die Empfindung nach landschaftlich wirkenden Bildern in den visuellen Resultaten ihrer Arbeit finden. Beide sind fasziniert von dem ersten Anblick einer Träne. Bei beiden ist die Faszination der Antrieb für das daraus entstehende Projekt. Ihre Arbeit verläuft in vielen Bereichen ähnlich, sei es bei der Wahl der Tränen oder dem Experimentieren mit Aufnahmemodi und technischen Möglichkeiten. Beide arbeiten mit Formatierung, Ästhetisierung, Systematisierung und Ökonomisierung, wobei einige dieser Aspekte bei Mikkers deutlich intensiver ausgeprägt sind. Bei beiden tauchen Tränen in ihrer Bildlichkeit auf, während die Praxis des Tränenvergießens in den Hintergrund gerät. Sie verbleiben als eingefrorene Objekte in einem Repräsentatinsmodus ohne die Perspektive der Performativität.

Während die Arbeit Fishers seit 2017 abgeschlossen ist, setzt Mikkers mit dem Wunsch nach neuen Erkenntnissen seine Arbeit fort. Zu welchen Ergebnissen er neben dem Erfolg der Vermarktung seiner Arbeiten kommen wird, bleibt gespannt abzuwarten.

Quellen: Rose-Lynn Fisher: https://www.rose-lynnfisher.com/bw-th-tt.pdf, Maurice Mikker: https://medium.com/micrograph-stories/the-stories-within-our-tears-fc64257e2acd